DELAWARE SPORTS IN THE 1900S

Football in the early 20th century was increasingly coming under attack for its brutality. Harvard and other schools, where the game was played at its highest level, dropped the sport altogether, demanding reforms. At the end of each year newspapers would dutifully print the death count from that season’s play. Delaware was not immune. Clarence Pierce, 20, of Claymont Street in Wilmington died after being kicked in the stomach during a football game in 1909. Pierce was one of 30 American men to perish on the gridiron that season.

Worse, for football lovers, than the violence on the field was the boring style of play which gripped the game. Seldom did fans enjoy even a ten-yard run, and following the ball was a nightmare as 22 players dissolved into an amorphous pile on every play. there were many mismatches between teams of disparate abilities and when squads of equal strength engaged a scoreless tie could be expected.

In this environment baseball grew into truly the national - and state - pastime. In Delaware the spring, summer and fall were filled with baseball and the winter was cherished as a time to speculate on future happenings on the diamond. During the season if fans weren’t attending a game they could be found gathered around bulletin boards in newspaper offices clamoring for inning-by-inning updates of local and national games. So many teams were clamoring for Wilmington baseball fields that a permit system for use of the diamonds was instituted in 1908.

Baseball was always a business, not a privilege for the Delaware sports fan. Any promoter of a baseball game could expect to incur the following expenses in 1905: rent for the grounds - $55; umpires - $15; balls -$12; ads -$30; grounds man - $10; police - $15; extras -$10. With an admission price of 25 cents an owner needed to attract 600 fans just to cover his fixed expenses. And that didn’t begin to cover his biggest costs - player salaries and guarantees to the visiting team.

With professional baseball virtually dormant in Delaware at the turn of the century the Brownson Library Association nursed play-for-pay ball back a game at a time in 1901. Each game that made a profit led to the next one being scheduled. The timing was right. With the game popularized by the consolidation of the best players into two major leagues, baseball was exploding. And by 1902 the best baseball in America outside the major league parks was being played in Wilmington. For the rest of the decade Delawareans could count on professional baseball in Wilmington and topflight amateur ball throughout the state.

A golfing group from the early 1900s at Wilmington Country Club.

Also enjoying a revival in popularity with the new century was horse racing. In 1901 the Wilmington Horse Show Association began leasing the former Wawaset Park grounds at Ninth Street and Woodlawn to stage fancy horse programs. To complement the judging contests the organizers added a few trotting races. Within a few years the races, now known as matinees, supplanted the horse shows. These weekly events became so popular Delaware became recognized as the Matinee Racing Capital of America.

Racing at the matinees was strictly an amateur affair. Expensively bred trotters shared the track with horses unhitched from milk wagons and delivery carts - all in quest of blue ribbons. The working stiffs were especially popular, none more so than William H., who went to the post more often than any other matinee horse. William H., winner of 53 blue ribbons with a lifetime mile mark of 2:38, raced until 1907 when he was knocked down and injured by a Peoples Railway trolley car at 2nd & Madison while on his day job. Meanwhile the best matinee horses from Wilmington were tabbed to compete in intercity races against Philadelphia, Trenton, and Baltimore.

The cream of Delaware society turned out for the matinees not just to watch but to compete. DuPont Company president T. Coleman du Pont was a prominent owner and timer and judge. In a heat in 1905 Howard T. Wallace, president of the Diamond State Steel Company, shattered his collarbone in a sulky accident during a race. Towards the end of the decade horse racing began to wane somewhat as these wealthy men turned their attention from swift horses to fast automobiles. The first auto races were roadability tests by the Delaware Automobile Association in which target times were assigned and each car hauled its full capacity of passengers as stated in the owners manual. Hundreds would turn out in downtown Wilmington to send off the roadsters on their round-trip outings to Kennett Square and Valley Forge and elsewhere.

Other motorsports were sweeping Delaware as well. Nick Charles, a shoemaker in Wilmington, attained a record motorcycle speed of 65 mph and inked a contract with the Indian Motorcycle Company as a professional rider. On the water Harry Richardson of Dover won national races in the Thousand Islands, New York, averaging 21 mph.

For the first time Delaware sports enthusiasts could find as many diversions indoors as out. Professional basketball came to the state for the first time and in its wake strong amateur teams like the Old Swedes and Brownson entertained new converts. Up to 1000 people would cheer on teams on the Grand Opera House stage and more traditional gyms.

Indoor track meets at the Wilmington YMCA featured the standard fare of dashes, jumping events and shot putting but also offered such novelties as rope climbs and potato races. In the window races competitors would strain against the clock as they squeezed through progressively smaller openings. For awhile indoor baseball - with 25-foot bases and a 6” ball - caught the fancy of fans at the Eleventh Street Rink.

Exciting the most fans was roller polo. The fast five-man game had been around since the skating craze of the 1880s but suddenly took Delaware by storm in 1907. That year the Orange Athletic Club travelled to Bridgeton, New Jersey and dispatched their hosts - winner of 31 straight games - for the first time ever on its home rink. Then an all-Wilmington aggregation fell only 3-1 to a Baltimore team that had never lost even a single game of roller polo.

When the Country Rink opened next to Brandywine Springs an intrastate rivalry began to fester among Wilmington teams and thousands attended the Delaware League matches. In 1909 Wilmington joined the Tri-State Roller Polo League with Baltimore and Atlantic City, skating before crowds of over 4000 when visiting the latter’s Steel Pier rink.

In 1904 boxing was re-born with Wednesday night exhibitions in The Casino at 50th and Market Streets. Fighters donned huge gloves so knockouts were rare but the bouts were lively. Boxing season ran from October to May and fans of the sweet science could count on a cleverly-promoted fight card each week. In 1907 the organizers moved the weekly matches out to the Country Rink. Now directly on the train line at Brandywine Springs it was not uncommon to find thousands of fight fans in attendance, especially when a Philadelphia fighter brought Pennsylvanians down in droves.

For those who preferred participating, bowling was the “prince of winter sports.” By 1906 there were four bowling leagues and 22 teams in Wilmington. That year the Wilmington Bowling Association sent an all-star team to the national tournament to represent Delaware for the first time. The lanes in Louisville, Kentucky played fast and the Wilmington kegelers suffered through 29 splits and 22 misses for a three-game, five man total of only 2428.

Bowling was the “prince of winter sports’ in Delaware in the early 1900s.

In singles play, however, William “Pop” Roach, the “Grand Old Man” of Wilmington bowling, tallied a 652 series to finish third nationally. Roach, a 190s-average bowler, was proprietor of the Academy Bowling Alley at Fifth and French Streets until ill health forced him to retire to his native San Antonio, Texas in 1907. He left Delaware with five perfect 300 games and a high series of 859 to his credit.

Delawareans could also see the best bowlers in the country when Wilmington was represented in the Eastern Bowling League. Lanes 12 and 13 at the Academy were groomed and reserved for the bowling greats from Philadelphia, Brooklyn, Newark and New York. In this fast competition Wilmington easily proved the equal of any city. In no sport did Delaware offer greater competition than trapshooting. The Delaware Trapshooting League, comprised of clubs from Claymont to Dover, produced several marksmen capable of breaking targets with America’s best. The major trapshoots held throughout the state attracted some of the largest sporting crowds in Delaware. In January 1904, when world champion Fred Gilbert competed at the Wawaset Gun Club, the throng was so large that fans had to go into the clubhouse in shifts to warm themselves by the coal stove.

The development of homebred shooting talent reached its apex in 1908 when Captain K.K.V. Casey of Wilmington won a silver medal in the 1000-yard shoot at the London Olympics - the first ever medalist from Delaware. Captain Casey, commanding officer of Company C in the First Delaware Infantry, was joined in the rifle matches at Bisley, England by fellow Delawarean John Hessian. Two days later another Delawarean on the 86-member American team, George Dole, son of Wilmington preacher George Henry Dole, aggressively wrestled through four English opponents to win gold in the 133-pound class - the first Olympic gold for Delaware.

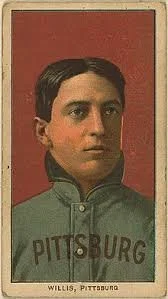

FIRST STATE SPORTS HERO OF THE DECADE: VIC WILLIS

Vic Willis won 248 games in a 13-year career. For many years every eligible pitcher with a career predominantly in the 20th century who won more than Willis’ 248 games was in baseball’s Hall of Fame except the Delaware hurler.

Vic Gassaway Willis was born in Cecil County in April 12, 1876, his colorful middle name appended from a character in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West troupe who his father had met while a traveling member. Young Willis started playing ball in Newark, competing for the Wilmington YMCA and Newark Academy as a teenager. After one year at Delaware College in Newark Willis left for Harrisburg and pro baseball. He helped Syracuse to a pennant in the Tri-State League in 1897.

Willis gained wide renown for his nasty curve ball, a pitch he called his Grapevine Sinker. He broke into the majors the next year and as a 22-year old rookie helped pitch the Boston team to the National League title with a 24-13 log. In 1899 he went 27-10 with a no-hitter, th elast thrown in the 19th century.

Vic Willis enjoyed his best seasons after being traded to the Pirates in 1906. He went 89-46 in the next four years and won a World Series title.

After an off-year in 1900 Willis came back to go 20-17 for a fifth place team. The next year the curveballer again won 27 games and set the National League record for complete games in this century with 45, a mark that still stands. After 1902 the Boston club became an awful team, always a threat to lose 100 games. Willis lost 25 of those games in 1904 despite an ERA of 2.81 and in 1905 he established a modern record for losses in a season with 29. Mercifully, Willis was shipped to Pittsburgh where he regained his winning form, tallying 20 or more victories for the next four years. In a series that matched the immortals Honus Wagner and Ty Cobb the Pirates and Willis won the World Series in 1909.

The next year Willis labored for the St. Louis Cardinals and when he was sold to Chicago before the 1911 season he retired. Willis returned to Delaware where he purchased the Washington House in Newark. He remained the proprietor until his death in 1947 of a stroke at the age of 71.

For many years Willis had more wins - 248 - than any pitcher not in the Baseball Hall of Fame. His eight 20-win seasons, and 50 shutouts were topped by fewer than a score of hurlers. The call from Cooperstown finally came for Vic Willis in 1995.

FINALLY, A SUCCCESSFUL LEAGUE

Throughout the 1800s leading Delaware sportsmen had tried to organize state sports teams into leagues. In baseball, in shooting, in football - all attempts failed. There were transportation problems, there were money difficulties, there were competitive disparities, there were petty jealousies.

It was not until 1901 that all dragons were slain and a sports league survived in Delaware from opening day to awards banquet with all members remaining intact to the end. The league that turned the trick was the Wilmington City Bowling League. Even then it stuttered through several false starts. Plans in 1900 were scuttled sending one of the primary movers in the enterprise, the Wilmington Whist Club, off to the Intercity Bowling League with Pennsylvania teams.

Finally in the summer of 1901 the Young Mens Republican Club, the Knights of Columbus, the Wilmington Bicycle Club and the YMCA bonded into an agreement for a wintertime league. The format was recognizable to any bowler of today: five-man teams, total pinfall deciding the winner over three games, every Thursday night. Each club hosted an equal number of matches on their home alleys.

The Republican Club won top honors with 15 wins in 18 weeks. The well-balanced team averaged 151.4 per man, yet anchor Henry Kurtz rolled only 157.4 per game. The Knights of Columbus, the tailender of the list with only five wins, toppled 143 pins per man, only eight pins a man shy of the champs.

The Wilmington City Bowling League was so successful a second team league formed in the middle of the season. Thereafter, leagues binding Delaware athletes became commonplace in many sports.

A SOCCER FANTASY

“Followers of the game of soccer declare that it will not be many years before their favorite game becomes a most popular sport. They have visions of great things which are about to come to pass. Visions of great amphitheaters which will hold tens of thousands of cheering soccer rooters. Visions of strongly entrenched professional soccer leagues, as great in scope perhaps as the present leagues of baseball...”

A newspaper article from the 1960s perhaps? The 1970s? The 1980s? The 2000s? No, 1907. For nearly a century it seems soccer aficionados have been waiting for their game to seize the imagination of the American public. Delaware did begin interstate competition in soccer in 1907 with teams from Philadelphia and New Jersey. But, while these contests were greatly enjoyed by the participants, the games were typically private affairs, attracting little interest among Delaware sports fans.

A HOTBED OF ROQUE

For a brief time at the turn of the century there was no better roque being played anywhere in America than the roque being played in Wilmington. Roque? Best described as a sort of scientific croquet, roque players crossed mallets at the private grounds of Dr. Benjamin Veasey at 1502 Franklin Street. Veasey was widely considered one of the top five or six roquers in the country.

Roque was so hot in the early 1900s it was contested at the St. Louis Olympic Games. America was the only country to field a team and there were only four competitors. That was it for roque in the Olympics.

As the Wilmington men polished their craft several became factors in national championship matches, mostly held in New England. James Hickman, a leather manufacturer, won laurels as the best Second Level player in American roque. Enough good players developed that the Wilmington Roque Club established permanent grounds at Jackson, Tenth and Adams streets.

The popularity of roque never expanded beyond this tiny enclave of devotees and disappeared from the scene with the passing of the Wilmington Roque Club. But for a fleeting moment Wilmington stood at the pinnacle of the roque world.