DELAWARE SPORTS IN THE 1970S

In 1971 the Wilmington Country Club hosted the United States Amateur golf championship, the first national tournament staged in Delaware since the 1913 U.S. Women’s Amateur. Gary Cowan, a Canadian, holed a memorable eagle 2 from the rough on the 72nd hole to win the championship. Trailing Cowan that day were a number of unknown young amateurs who would go on to greater fame, golfers such as Gil Morgan, Bruce Lietzke, Howard Twitty and four who would one day win a major championship - Bill Rogers, Andy North, Ben Crenshaw and Tom Kite.

The 1970s in Delaware sports were like that. A time to look ahead. Professional baseball in the state was buried deep in the obituary files, minor league football had rasped its last breath and basketball was gasping through one final embarrassing death throe. But there was plenty of sporting potential on display.

The greatest crop of Delaware professional football players - Randy White, Steve Watson, Joe Campbell, Anthony Anderson - were all playing high school football in the Seventies. And it was a good decade for scholastic athletes. Chris Moore of Lake Forest broke the state high school scoring record in basketball and Purnell Ayers of Cape Henlopen eclipsed Moore’s mark. Jenni Franks, a Mt. Pleasant junior, broke world swimming records. A college student, Blaise Giroso a Brandywine High graduate, won the first of a record ten Delaware Amateur golf championships in 1979. In Newark the University of Delaware won three Division II national football championships, in the polls in 1971 and 1972 and in the playoffs in 1979.

Another organization looking ahead was the Delaware Special Olympics, the state chapter of international competitions for the mentally handicapped, which began training and competing in 1971. The program would eventually expand to provide tournaments in 13 sports.

By the mid-seventies eleven Delaware high school baseball players had graduated to the minor leagues but none was in the majors. Delaware did, however, sport a professional softball player. Audie Kujala, one of the University of Delaware’s all-time athletes who batted .530 in her Blue Hen career, starred in the outfield for the Connecticut Falcons in the short-lived women’s professional league. She was the AIAW softball player of the year in 1977.

Horse racing was less popular than it had ever been and there was even talk of bringing jai alai to Wilmington. It was a manifestation of a trend away from spectating and towards participation. State recreation facilities were expanding like never before. Multi-use facilities like the showcase Delcastle Recreation Complex in northern Delaware became magnets for softball players, tennis players, soccer players and volleyball players. More and more, if Delawareans wanted to watch sports they only had to follow their neighbors and friends to the games.

FIRST STATE SPORTS HERO OF THE DECADE: RANDY WHITE

The most honored athlete ever to come out of Delaware never made All-State during his high school career. No matter. Such an award would be lost in Randy White’s brimming trophy case. By the time White ended his 14-year Dallas Cowboy career in 1989 he had been an All-Pro defensive tackle eight times, a Super Bowl co-MVP and a certain Hall-of-Famer.

Randy White was born in Pittsburgh before his father, a butcher, brought the family to Dunlinden Acres in Delaware. At McKean High School White was a bruising fullback and standout on defense but was unable to lift his team to a winning record. Consequently he was never singled out for anything better than 2nd-team All-State honors, but he was invited to the annual Blue-Gold All-Star game.

Although Delaware All-State voters were singularly unimpressed White stirred the passion of college recruiters. Still, he had pretty well been wrapped up by ace University of Maryland scout Dim Montero since the 10th grade. At College Park White rapidly matured, sculpting 248 pounds onto his 6’4” frame. A fanatic for work - even among those who considered themselves fanatics for work - he improved his bench press to 450 pounds without losing a step from his 4.6 speed in the 40-yard dash. After his junior year in 1973 White was named to the Associated Press All-America first team as a defensive end.

As White’s fortunes climbed, so did Maryland’s. The Terrapins made their first postseason appearance since 1955 in the Peach Bowl in 1973. The next year it was off to the Liberty Bowl and White won the coveted Outland Trophy, emblematic of the nation’s top lineman. He was the second player chosen in the 1975 NFL draft, going to the Dallas Cowboys with a pick obtained from the New York Giants.

At Dallas, White seemed almost too talented for his own good. Where do you play someone that quick, yet that strong; that big, yet that agile? For two seasons White languished as a special teams player and reserve middle linebacker, picking up pass receivers coming out of the backfield. In 1977 Coach Tom Landry switched White to the defensive line and he immediately became one of the NFL’s premier defensive performers. He was voted Co-MVP with teammate Harvey Martin in Super Bowl XII following the 1977 season for helping the Cowboys lasso the Denver Broncos 27-10.

The next year White was NFC Defensive Player of the Year after making 123 tackles, 16 of them quarterback sacks. He would be selected to every Pro Bowl from 1977 to 1985. White’s legendary intensity earned him the monicker “The Manster,” part man, part monster. Landry once remarked, “I don’t think I’ve ever coached a player who brought everything to the field on every play like Randy White.”

After 14 years White retired to the farm. Growing up White had never lived on a farm but shortly after visiting teammates’ ranches in Texas he purchased a 21-acre spread of his own in the rolling Chester County hills. His record of 1100 tackles and 114 sacks guaranteed his installment as Delaware’s first member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio. But still no Delaware All-State football player has been a Hall-of-Famer.

FIRST STATE OF MASCOTS

Dave Raymond, son of Delaware football coach Tubby Raymond, created sports mascot history as the personality inside the impish Phillie Phanatic for 16 years. But before there was a Phillie Phanatic there was a Lawrence Hunn.

Hunn, from Dover, was a senior at Georgia State College working part-time for the Explorer Scouts in 1966 when the newly imported Atlanta Braves contacted the Scouts looking for someone to do an Indian dance at Braves games. Hunn took the assignment and in the dark ages before political correctness set out to create the most authentic woodland Indian he could.

He dressed in leggings, a beaded apron and vest, black moccasins and feather decorations - all topped by a gaudy horsehair headpiece. In an attempt to appear fearsome, and hide an un-Indian-like mustache, Hunn smeared his face with blue war paint. Chief Noc-A-Homa, as the Braves’ mascot came to be affectionately known, perched inside a teepee on a platform beyond the leftfield fence during games, emerging amidst a plume of smoke to greet every Brave home run with a celebratory war dance. For most of the game Hunn, a marketing major, would hide in the teepee reading the Wall Street Journal.

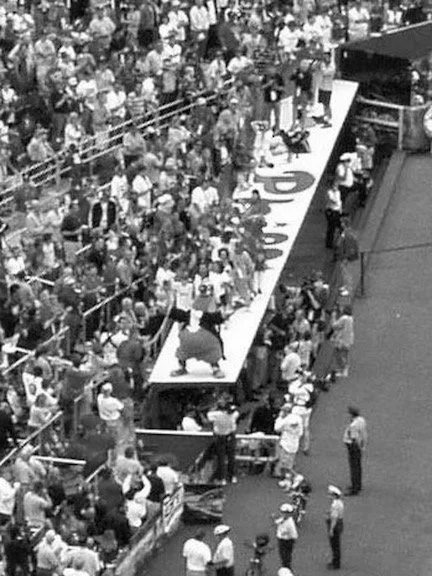

Raymond, a kicker for the Delaware Blue Hens, was a student working as a clerk in the Phillies promotion offices when Bill Giles asked if he would climb inside a new costume and appear at Veterans Stadium during Phillies games. The character had no name and the Phillies did no special promotion prior to Raymond’s first appearance on April 25, 1978.

If there was something going on in the stands at Veterans Stadium in the 1970s it was likely the Phillie Phanatic was in the middle of it.

Raymond was given no instructions. Phillie experience with mascots heretofore had been limited to those staid patriots Philadelphia Phil and Phyllis. Raymond was paid $25 a game to bound on the field and through the stands and see how fans reacted. He slipped into the 35-pound costume and made the green furry creature with the megaphone mouth and bulging eyes a Philadelphia institution.

Raymond continued in the role of the Phanatic for 16 years before bowing out after the Phillies’ National League Championship year of 1993. In that time he missed only eight home games. Away from Veterans Stadium he made more than 250 appearances annually and reaped an income estimated at over $100,000. In his wake Raymond, along with the Chicken, spawned a legion of less-talented imitators in sport’s Era of the Mascot. To wit, the Phanatic was voted ‘best mascot ever’ by Sports Illustrated for Kids and Sports Illustrated.

A SWING AT SOCCER

For anyone who has ever driven around residential Delaware on a summer evening and seen the thousands of kids playing soccer on area fields the state would appear to be a natural for professional soccer. The first to try it were the Delaware Wings in the American Soccer League in 1972.

The Wings were founded with the philosophy of giving Delaware players a chance to play soccer after college and developing local talent. While most teams in the ASL relied on foreign talent the Wings started nine or ten Americans. Playing under this experience handicap the Wings enjoyed a successful 5-4-1 first season and coach Ron Gilbert was named ASL Coach of the Year.

In 1973, now playing in Baynard Stadium, the Wings completed a respectable 5-7-2 season, narrowly missing the playoffs. Attendance averaged between 500 and 700 but after an 0-2 start in 1974 only 160 were on hand for the home opener. The talent discrepancy began to overwhelm the Wings and coach Al Barrish. The Wings finished with the worst record in league history, 1-14-2, and that lonely win was by forfeit. The only bright spot was forward Charlie Ducelli, a second-team All-League forward, who was fourth in the ASL in scoring with 9 goals and 3 assists.

The Wings averaged only 407 fans in 1974 while its big league opponents were drawing ten times that number. The franchise expired in 1975 but a foundation had been laid for big-time soccer in Delaware. When Baynard Stadium was the site for a United States-Mexico Olympic Regional Soccer Elimination later that year a near-capacity 4700 fans packed the stands, even though the United States was already eliminated from the competition. Mexico beat the inexperienced Americans 4-2 in Wilmington, but had to come from behind twice to do so.

The evolution of pro soccer was stalled for almost two decades until the formation of the Delaware Wizards in 1993, playing as one of 43 teams in the more localized U.S. International Soccer League. The Wizards, like the Wings, bore a heavy Delaware flavor. On their opening roster the Wizards had 21 players, more than half of whom played either high school or college soccer in the state.

The Wizards finished 11-8 in the Atlantic Division, making the playoffs in their first year where Delaware lost to Greensboro, the eventual league champion. The Wizards pulled 3000 fans to each game at Glasgow Stadium and the team earned recognition as a model franchise in the USISL.

ROLLING THROUGH OBSCURITY

What is it about ice? Strap on skates with a blade and swirl and swoop with your partner and people line up and television lights blaze. But perform the same routines on wheels and the world will try and stifle a collective yawn. Over the years Delaware roller skaters have built as enviable a record as their ice skating cousins but there have been no parades, no streets renamed and little recognition.

Warren Danner was Delaware roller skating’s Ron Ludington. He coached Jane Panky and Richard Horne to the 1972 World Dance Championship. Panky and Horne defected to the ice themselves after 1972 and Danner orchestrated the fortunes of Concord High graduate James Stephens and Jane Perucchio of Cleveland Heights, Ohio. For several months the pair could train only on weekends as the 16 year-old Perucchio commuted from Ohio. But with a summer of regular work the young pair captured the 1973 International Roller Dance title.

The next world champions from Delaware were Anna Marie Danks and Scott Myers who trained at the Christiana Skating Center in the late 1980s. Roller skating is now on the verge of being an Olympic sport. When that happens don’t be surprised if Delaware’s roller skaters bring the state as much recognition as its ice skaters.

THE FIRST FAMILY OF DELAWARE TENNIS

Of all the sports Delaware has made less national impact in tennis than any other - with one glaring exception, the Vosters family. In 1964 and in 1988 the Vosters were named the United States Tennis Association Family of the Year. The national recognition is bestowed annually to the family that has done the most to promote amateur tennis in the country, especially on a volunteer basis. But the Vosters play a bit too.

Madge “Bunny” Vosters, the matriarch of Delaware’s most distinguished tennis clan, began playing with her family as a teenager in the 1930s when she became a nationally ranked junior player in Pennsylvania. At Ursinus College she wontwo Eastern States Clay Court Singles championships and was an All-American reserve in field hockey. Vosters also played basketball.

In 1942 Vosters, known for “a nearly unretrievable drop shot,” reached her highest United States Tennis Association national ranking - No. 9 - at the age of 23.

No one ever won as many tennis trophies in Delaware as Bunny Vosters.

She moved to Delaware in 1952 and the next year she was state champion. Her eldest daughter, Nina, won 16 letters at Friends School and was nationally ranked in Girls 18 singles in 1963. Bunny and Nina won two national mother/daughter titles.

Meanwhile, younger daughter Gretchen was polishing her game. Gretchen Vosters won her first Delaware State Women’s Tennis Championship in 1967. Lyndon Johnson was President. She retired, unbeaten in state play, 20 years and five presidents later. In winning 20 consecutive Delaware titles she lost only one set in the finals, in 1972 to Connie Von Housen. In that time she dropped only 54 games in 41 sets of championship play. She dispatched 13 different aspirants to the throne during her reign.

Unlike many champions Gretchen Vosters Spruance was hardly obsessed - or impressed - by her accomplishments. She had two children during “The Streak.” She virtually stopped playing all competitive singles and often had to be goaded into defending the state title by her husband and mother. Her favorite tennis was with her mother. Bunny and Gretchen won 24 national mother/daughter titles. In the winter months Spruance played squash, well enough to win five national singles and five national doubles championships. Bunny and Nina also won national doubles squash titles.

In 1981 Bunny Vosters won her first national singles crown. Playing on the home turf of Wilmington Country Club the unseeded Vosters defused top-ranked Betty Pratt’s drop shot to prevail 6-7, 7-6, 6-4 to capture the USTA Womens 55 and Over Grass Court Championship. There would be more age division titles for Vosters. The Delaware Sports Hall of Fame, for one, couldn’t wait for her to retire. They waived the normal five years of retirement rule for qualification and inducted Bunny Vosters in 1980.

WHEN THERE WAS NO SEMI ABOUT IT

Pro baseball is not what it used to be. Once the undisputed “national pastime” the sport has been steamrolled by football in popularity. So imagine how vital “semi-pro” baseball must be. Games for the eight teams in the Delaware Semi-Pro Baseball League attract about as many spectators as a Sunday afternoon softball kegger.

But such was not always the case. The league formed in 1941 and developed teams and legends every bit as colorful as those toiling in the bigs. Any recounting of the Delaware Semi-Pro league must begin with John Hickman, whose Parkway team made the playoffs for 38 consecutive years. His lowest finish during that time was 4th place, of 11 teams, in 1956.

Under Hickman Parkway won 16 league pennants and 13 playoff titles. There were eight straight pennants from 1965-1972. The heyday of Parkway was the heyday of the semi-pro baseball in Delaware as other teams chased Hickman’s champions. In the 1960s playoff games at Rockford Park, Canby Park and especially 18th & Van Buren Streets would routinely attract crowds over 2000 (there were many seasons in the 1960s when the Phillies would not draw 10,000 fans a game to Connie Mack Stadium).

Teams featured many of the top college players from around the East. Many semi-pro players were on either side of major league careers: Chris Short, Jack Crimian, John Wockenfuss, Dave May. Parkway’s greatest player was Bob Immediato, who played into his 50s. The 6’2”, 190-pound first baseman joined Hickman in 1962, after three years in the Cleveland Indian farm system. With Parkway he established career league marks in hits and RBI.

But despite Parkway’s success many longtime league observers consier the team assembled by Brooks Armored Car, Parkway’s great rival, in 1963 to be the finest semi-pro team to ever take a Delaware diamond.

That year Brooks’ third baseman-manager Lou Romanoli mounted his greatest challenge to Parkway’s dominance. He rounded up three former major league pitchers for his rotation - Crimian, Bob Davis and Ray Narleski, who at 34 years of age was only five years removed from winning 13 games with the Cleveland Indians.

To bolster his line-up Romanoli recruited Ruly Carpenter, the Yalie future Phillies owner who had led the Ivy League in batting, and ex-big leaguer Harry “The Horse” Anderson. Anderson was only 32 years old and had finished 18th in MVP voting in 1958 when he belted 23 home runs to abet a .301 batting average.

The two nines clashed in the championship finals and with fans overflowing the bleachers and hanging from tree branches Brooks swept Parkway four games to none.

By 1988 Parkway was suddenly not only out of the playoffs entirely but struggling to win a game - and field a team. The misfortunes piled up, growing so bad that Hickman, then in his seventies, played right field in one game to prevent a forfeit. Six games into the 1990 season the franchise disbanded.

It was only a precursor to the fate of the league as a whole. By the 1980s major league games were on television every night and fresh air and good semi-pro baseball on Wilmington fields was no longer the attraction it once was. And shortly there would be other professional baseball in town as well.

DELAWARE SPORTS WORDS

When Al Cartwright, then 29 years old, walked into the newsroom of the Journal Every Evening in 1947 to take over the job as sports editor he looked around and saw only one other full-time member of the sports department. Cartwright was born and raised in Reading, Pennsylvania, a sports town much like Wilmington that harbored major league ambitions while orbiting in the sphere of Philadelphia, and he knew how important first-rate reporting was to readers. Cartwright himself was most recently of the Philadelphia Record and his immediate goal for Wilmington was to provide professional coverage of local sports.

To create a big league sports page required talent and Al Cartwright had that in spades. His sports column was called “A La Carte” and he wrote about anything and everything, usually flecked with equal parts insight and humor. He injected his columns with fictional characters such as “Blewynn Gold,” a purported University of Delaware graduate Class of 1890, who “had seen them all” and “Kenton Sussex” who picked horses. In 1950 the National Headliners Club recognized Cartwright as America’s “Most Consistently Outstanding” sports columnist.

With Cartwright, small-town Wilmington had a reserved seat at the nation’s top sporting events. He would cover World Series games and attended the Olympics in Tokyo in 1964 and Mexico City in 1968. But his greatest impact on Delaware sports came at home. Many of the state sporting institutions that are taken for granted came about because Cartwright championed them in the newspaper: high school athletic conferences, Little League sports, the Delaware State Golf Association and organized swimming leagues among the suburban pools that sprang up in the 1950s.

All-state teams? Cartwright’s idea. The Delaware Sports Hall of Fame? Cartwright again. He started the Wilmington Sportswriters and Broadcasters Association and in 1950 the organization began giving out its coveted award to the outstanding sports performer of the previous year. The award was named for John J. Brady, who had segued from a semi-professional football and baseball manager into the sports editor’s chair at the Morning News in 1924 and was the print voice of Delaware sports for over twenty years.

Cartwright set about giving Wilmington a sports department the envy of cities many times the size of Wilmington. In 1950 he recruited Izzy Katzman from the Harrisburg Patriot. Katzman was nimble enough to write on any sport but he found his sweet spot when the Brandywine Raceway opened on Naamans Road in 1953. When the United States Harness Writers Association began giving out its John Hervey Awards for excellence in standardbred jornalism in 1962 Katzman picked up one of those. In 1994 he was inducted into the Harness Racing Hall of Fame, in the “Writers Corner.” Katzman stayed at the News-Journal for 36 years.

When Cartwright brought Matt Zabitka down from Delaware County in 1962 his mandate was “to increase local coverage and maintain rapport with news sources.” Zabitka was a Chester, Pennsylvania native who had already done enough work as a sports talker on WDRF and a writer with the Delaware County Daily Times to earn him enshrinement in the Delaware County Sports Hall of Fame in 1978. His ubiquitous coverage of local sports for 40 years would land Zabitka in the Delaware Sports Hall of Fame as well.

Since Cartwright created the modern sports section in Delaware papers such devotion to the state athletic scene is not uncommon. Chuck Durante, who started writing about Delaware sports as a stringer for the Philadelphia Inquirer while at Villanova Law School in the 1970s, has covered First State athletes for over four decades. He served as president of the Delaware Sportswriters and Broadcasters Association for 15 years. Since leaving the University of Delaware in 1980, Kevin Tresolini’s byline has appeared in the News Journal’s sports section for over 35 years.

But the Al Cartwright sportswriting tree branches far beyond Delaware borders. The writing talent he brought to Delaware took root in markets across the country and quite a few of those who read him took up writing because of his columns. Gary Smith was born in Lewes in 1953, one of nine children in residence in a rambling five-bedroom house. At the age of 16 he was working as a clerk at the News-Journal and the paper was a launching pad that landed Smith at Sports Illustrated in 1982. His stories were included in the Best American Sportswriting anthologies, more than any other scribe, and he won four National Magazine Awards. Before retiring in 2015 Smith was hailed as America’s finest magazine writer, who just happened to be working in sports.

Harley Ryan Bodley, a native of Smyrna, took his fresh University of Delaware sheepskin to the Delaware State News in 1958 to cover baseball. He came to the News-Journal in 1960 and worked his way through the sports department to become sports editor in 1969 when Cartwright took a sabbatical to work for his beloved Philadelphia Phillies who were making a transition from Connie Mack Stadium to Veterans Stadium. Hal Bodley would remain as sports editor until 1982 when he assumed the position of baseball editor for USA Today. Including his 22 years at the News-Journal, Bodley would cover 43 World Series and 41 All-Star Games and watch an estimated 36,000 innings of major league baseball in the guise of a reporter. Bodley won 30 regional and national writing awards, including a dozen times named “Delaware Sportswriter of the Year,” as the most honored sportswriter in Delaware history.

DELAWARE SPORTS VOICES

The first radio programs in Delaware crackled across the airwaves on July 22, 1922 from the WDEL studios. That year listeners could tune in a nightly sports show presented by Herman “Hoim” Reitzes, who was working his way through the University of Delaware. In the coming decades Reitzes would provide listeners their first coverage of live Delaware sports with play-by-play of University of Delaware football and the Wilmington Clippers. In the 1940s Reitzes would travel down to Rock Hill, South Carolina and file reports from the Blue Rocks’ spring training camp.

In March of 1949 a sister outlet of WDEL went on the air - WDEL-TV, Channel 7. The low-power transmission from the broadcast center on Shipley Road in northern Delaware was so weak it caused no interference with Philadelphia stations only 30 miles away. Even so, Delaware’s first television channel would be shuffled off to Channel 12 by 1951. The station’s first sports director, signing on after stints with the United States Navy and Temple University, was George Frick. In 1951 he launched a nightly 15-minute sports show called “The Sporting Scene” that featured interviews and footage from local sports statewide. The TV Guide named it the “Best New TV Sports Show in the Delaware Valley.”

After Channel 12 ceased commercial operations Frick continued to be active in Delaware sports, including a three-day-a-week column for the Delaware State News - “Frick’s Picks.” But he was not finished with silver-tongued oratory. There were live broadcasts from the Brandywine Raceway, Dover sports coverage for WDOV, and eleven years as the starter and announcer for the McDonalds LPGA golf tournament. In 2005 when Wesley College refurbished the press box at Scott D. Miller Stadium it was dedicated to George L. Frick.

In Newark, the pressbox of Tubby Raymond Field at Delaware Stadium is a memorial to Bob Kelley, the “Voice of University of Delaware Football.” Kelley was behind the microphone for 378 consecutive Blue Hen football games from 1950 until his death from leukemia at the age of 64 in 1988. Kelley was also the radio broadcaster for Blue Hen basketball from 1962 until 1979. Kelley had migrated to Delaware in 1950 as a sportswriter when his New York City newspaper, The Sun, shuttered after 117 years of operation. Kelley wrote for the Wilmington Morning News and handled publicity for Delaware Park for almost two decades. Nineteen times Bob Kelley was honored as Delaware’s “Sportscaster of the Year.”

The Bob Kelley Pressbox at the University of Delaware

During the 1960s and 1980s Kelley teamed with Bill Pheiffer who got started in radio and television in 1949. As sports director for WDEL for over 30 years Pheiffer was a familiar voice on Wilmington Blue Bombers basketball, Salesianum football and Big 5 basketball games from the Palestra in Philadelphia. Pheiffer called horse races at Brandywine, Delaware Park and Fair Hill. He also manned the sports editor desk at Delaware Today magazine. He once estimated that he had broadcast more than 1000 professional, collegiate and high school games at over 200 venues in 32 states. After retiring from WDEL in 1989 Pheiffer continued working Blue Hen football and basketball until 1999.

For a spell in the 1970s, Bob Kelley’s partner in the booth was Tom Mees, a Springfield, Pennsylvania native who got his start doing football play-by-play on the the University of Delaware student-run station. After graduating in 1972, he became sports director at WILM for six years, joining Kelley for football and basketball broadcasts. In 1979 Mees broke nationally as one of the original sports anchors at ESPN, where he worked until drowning in a swimming pool accident in 1996.

Few voices are more familiar in Delaware than Marv Bachrad’s. Bachrad was already in the Communicators’ Corner of the Harness Racing Hall of Fame before he went to work with Dover Downs in 1997. Bachrad graduated from Norristown High School in Pennsylvania in 1953 and began working at local radio stations, including a two-year hitch running an Armed Forces radio station. As a local television reporter in Philadelphia he was a fixture on 76ers and Big Five games. Bachrad was a charter member of the United States Harness Writer’s Association 1n 1963 and took over public relations duty at Garden State Park in New Jersey in 1975 and pioneered the use of the fax machine for disseminating race results. Bachrad took over the same duties at Brandywine Raceway in 1979 until the track’s closing in 1989 before taking his Hall of Fame credentials to Dover.