AUTO RACING IN DELAWARE

THE GREEN FLAG

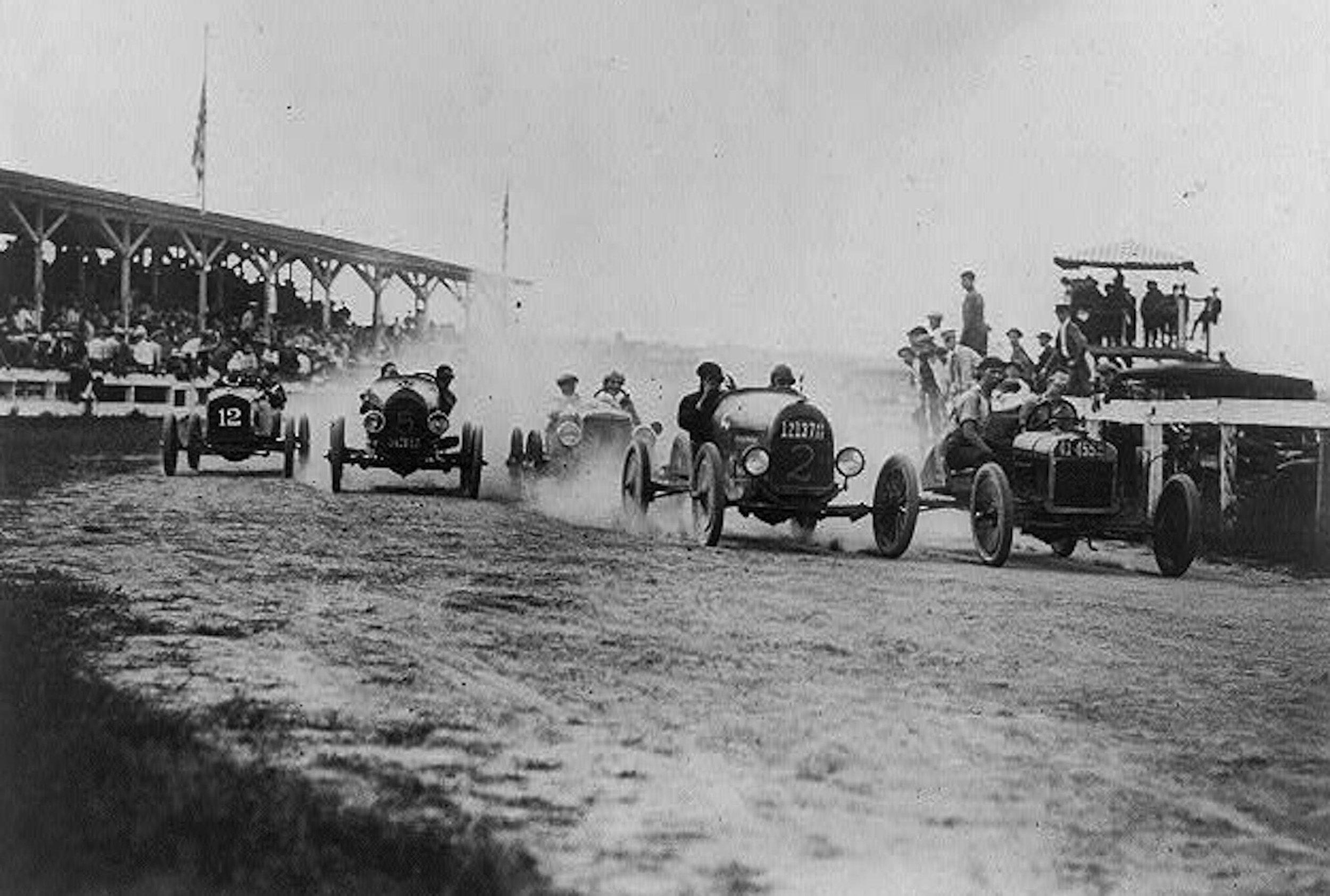

Auto racing first supplanted horse racing at the Delaware State Fair in Elsmere in 1919. There were many pile-ups on the non-banked dirt horse track and many of the 5000 in attendance agreed with the newspaper accounts that it was “greatest auto show ever witnessed in Delaware.” At Harrington, the auto races were the highlight of the Kent-Sussex Fair.

By 1925 the turns at the Elsmere track were banked and the dirt was rolled hard. Manager Dave Coxe staged regular programs that included time trials, 5-mile races and 10-mile features. There were 70 deaths in auto racing in 1924 but none at the Delaware tracks.

Through the 1930s the only night racing in the East was at Elsmere. For a time midget racing was the biggest speed show in Delaware but it gradually gave way to the excitement of the big stock cars. The old speedway at Elsmere would not see the age of stock cars, however. In 1939 the track gave way to the Elsmere Gardens housing project.

Most Delaware sports fans had never seen anything as exciting as early auto racing on the state’s dirt tracks.

In Delaware, as elsewhere in America, stock car racing took root in rural areas. In the 1940s there were four state tracks; all downstate, in Little Creek, Bridgeville, Magnolia and Georgetown. Georgetown was the biggest and Sunday races would attract drivers from as far away as Mississippi for $500 purses. More than 3000 fans would watch the factory cars skid around the half-mile oval at speeds averaging 65 mph. Some could click over 100 mph on the straightaways. Top Drivers included Russ Bennett of Rehoboth, Bob Burkhart of Wilmington and Johnny Martin of Milford.

In the early 1950s stock car racing spread northward. Augustine Beach Speedway opened and enough Wilmingtonians drove the 17 miles south that the Wilmington Speedway was built on the Du Pont Parkway in 1952. That year the new asphalt plant hosted a $3000 NASCAR event on the Grand Circuit. A capacity crowd of 5360 turned out for Delaware’s first national stock car event. Twenty-five drivers from seven states roared off the starting line and followed 50-year old Pappy Hough of Paterson, New Jersey to the checkered flag.

The races at Wilmington Speedway were the best attended Delaware sporting events, save for Delaware Park and Brandywine Raceway. Capitol Speedway joined the state roster of stock car tracks when it opened on Route 113 in Cheswold. It was all a warm-up act for the super speedway at Dover Downs.

DELAWARE’S INDY STAR

One of the racers who emerged from the Elsmere driving wars was Russell Snowberger. Snowberger was born in Denton, Maryland in 1901 but raised in Bridgeville. He started racing at Harrington in 1921 and set the half-mile track record at Elsmere with a lap in 31.3 seconds. In 1927 Snowberger, then a Philadelphia resident, got a car in the Indianapolis 500 as a relief driver and was in the starting line-up for 1928. His Marmon front-drive racer was forced out of the race on only the fourth lap with mechanical problems but as a relief rider for Jimmy Gleason he led the race for thirteen laps.

Snowberger went on to specialize in revamping stock cars into Indy cars. In 1930 he spent $156 to prepare a production car for the Indianapolis 500 and came in 8th against $25,000 cars. The next year he won the pole position for the Memorial Day classic and wound up the race 5th. The next three years he came in 5th, 8th and 8th again. In an era when fewer than half the starters completed the 500 miles Snowberger was the only driver to finish in the money five straight years. He won $17,300 for those five races.

Russell Snowberger was the fourth-ranked American driver in 1931. For the 1932 Indianapolis 500 he selected this Hupmobile Eight Comet for his ride.

Busy most of the year at his day job as an engine inspector at the Packard Plant in Detroit, the 500 was the only race he entered. Although several times he was running among the leaders deep into the race Snowberger never again finished as high as fifth.

By 1947 Snowberger had made 15 starts in the Indianapolis 500. Only a handful of drivers had made the Memorial Day run more times. That year he covered only 74 laps. It was his final appearance at the Brickyard. His last competitive turn behind the wheel came in the Pikes Peak Hill Climb in Colorado in 1949. After putting down his goggles he signed on as chief mechanic for the Federal Engineering team running out of Detroit before retiring from racing in 1960.

THE MIDGETS

In 1935 the Delaware Sports Center was chartered to promote sports in the state, including wrestling and boxing. But the main activity was to be midget auto racing. This exciting spectacle had started on the west coast and the racing plant on Route 13, one mile south of Hares Corner, was the first track built especially for midget racing east of the Mississippi River.

Former driver and promoter Dave Coxe graduated from his pioneering work at Elsmere to beat the drum for the midgets. The track was 1/5 mile around and most races featured 20 laps of non-stop action. There was seating for 5000 and room for another 5000 at the Thursday evening events under 90,000 watts of light.

Admission was 50 cents and 5000 fans lined up to get in for the debut as drivers swathed in shoulder pads and helmets and heavy boots (to protect from the hot oil and water spraying from broken hoses) squeezed into the little racers. Coxe’s ads promised “spills, thrills and chills” and no one left disappointed. The cars crashed into the infield only to reemerge time and again. Wheels locked and cars flipped end over end. The powerful, noisy engines added to the flavor of the evening. The crowd loved it. Most everybody agreed it was the best sport to come to Delaware in a long time.

The first card of nine events was dominated by locally built and piloted cars. Wilmington driver Lee Minnick carried off several prizes but the action quickly attracted the big-timers from New York who started to sweep all the awards. Coxe’s promotions kept the track humming; he brought in real midgets under 3’5” to race the little cars and on July 4 he featured Indianapolis 500 drivers.

Midget racing continued at Hares Corner for several more years. Tragedy occurred in 1938 when 38-year old Bob Harper of Chester, the starter, was killed while flagging the field to signal the final lap. Danny Goss coming in front of the grandstand in heavy dust never saw Harper and struck him going 65 mph, sending the body 100 feet down the track in front of 2000 spectators. Ironically Harper’s brother was on that final lap on his way to winning the race.

The midgets gave way to the “big cars,” the stock cars, before World War II but racing fans did not soon forget their summer evenings with the spills, thrills and chills of the midget racers.

DELAWARE DRIVERS

Johnny Pierson. At the age of 24 in 1941 Pierson created a sensation on the midget racing circuit by winning the Eastern championship crown. Pierson was a student in auto mechanics at Brown Vocational School in Wilmington and working part-time in a city garage when he got an offer to drive in 1938. Working his way through the circuit he drove every night, maybe five races a night, earning $250 a week at the pinnacle of his sport.

Bob Mattson. Mattson was a native Californian who came to Delaware during World War II to work in the shipyards. He settled in Wilmington, building race cars in his garage at 1301 Philadelphia Pike. Mattson was the second leading stock car driver in the East in 1947 and third in 1948 when he won 5 of 38 races. He attempted to qualify for the Indianapolis 500 in 1949 but failed after he cracked up his car in a race back home in California. Mattson returned to the dirt tracks but died tragically several months later after locking wheels and flying over an embankment in a race in Salem, Indiana.

Lou Johnson. Johnson began racing stock cars on dirt tracks in the 1940s, including Augustine and Georgetown in Delaware. Over the next quarter-century he travelled to tracks up and down the East Coast during the boom time of sprint car racing. The loosely organized circuit developed into the United Racing Club and Johnson won its driving championship three times.

George Alderman. After two years at the University of Delaware and two in the Army, Newark native George Alderman began racing cars in 1956. His specialty was road racing and he soon won the Sports Car Club of America driving championship. In 1960 Alderman was the Formula III driving champion at age 29. An expert mechanic, Alderman continued winning races on the sports car circuits for three decades.

Brett Lunger. Princeton political science student by day, race driver by night. Brett Lunger was home in Wilmington for the summer in the 1960s when he happened on a couple of evening auto races. Hooked by the competition he began asking questions and came under the tutelage of George Alderman. In his first season, while still in school in 1966, Lunger was competing in the Canadian American Challenge Cup Series, the premiere road-racing series in North America. After a tour of duty in Vietnam in 1969-70 Lunger decided to make a career of auto racing. At first he tried being an owner-driver but soon concluded his best opportunities lay in driving. He went to Europe, apprenticed against some of the top road racers in the world, weathered the oil crisis and emerged in 1975 as a Grand Prix driver. In 1976, as the only American-born driver in Formula One, Lunger finished in the top ten four times.

HOME OF THE MONSTER MILE

In 1940, Melvin Joseph went to work with a sixth grade education, a dump truck and a shovel. He was 19 years old. 1949 became a big year - he became a partner in a downstate Ford dealership, he scored his first big contract for Melvin L. Joseph Construction Co. and he got involved in racing by building the Georgetown Speedway. Joseph was known to break a few speed limits on the back roads of Sussex County in his souped-up Mercurys.

Joseph was a pioneer in early NASCAR and a fixture on the sands of Daytona Beach in the 1950s. All his cars and, later, horses, carried the number 49 from his “lucky” year. He set his sights on designing and building a dual track for fast horses and fast cars.

That dream was Dover Downs, whichopened in 1969 as America’s first multi-purpose sports complex, a distinction it retains today. The busy agenda called for thoroughbred and standardbred racing on the interior 5/8 mile oval and world-class auto racing on the outside one-mile track. For auto racing Dover Downs boasted a new design principle - “variable degree,” which promoted a smooth transition from straights to high-banked turns that allowed drivers to reach unheard of speeds on the one-mile lap. Hence the Dover track’s nickname: “The Monster Mile.”

The first event at Dover Downs was the Mid-Atlantic 300, the longest scheduled race in United States Auto Club history. Lining up in the starting grid were A.J. Foyt, Bobby Unser, Al Unser and other Indy stars. Foyt won the race which was halted after only 158 laps due to heavy rains. Later that year Andy Granatelli captured the Dover 200 over Mario Andretti and Gordon Johncock.

Richard Petty christened the new speedway for NASCAR racing with a victory in the Mason-Dixon 300 on July 6, 1969. “The King” averaged 115.772 mph for the 300 laps in his Ford Torino Talladega and the win was the first of seven trips under the checkered flag for Petty at Dover, tying him with Bobby Allison for the most NASCAR wins in Delaware.

Jimmie Johnson pushed the record to eight in 2013. Two years later Johnson became only the fifth driver in NASCAR history with at least ten wins at a single track when he captured the spring event. When 2015 ended Johnson had led 2,999 laps at the Speedway.

Since 1971 the Dover Downs International Speedway has hosted two NASCAR Winston Cup stock car races each year. The two race weekends are by far the largest spectator sporting events in Delaware, with the equivalent of one-half the state’s population attending Friday qualifying sessions, the 200-mile NASCAR Busch series races on Saturday and the classic 500-mile tests on race Sunday.

In 1995 Dover became the first supersweedway in NASCAR to be paved with concrete, providing a faster and more competitive racing surface. In 1997, with the Sprint Cup race shortened from 500 miles to 400, Mark Martin established a race record by averaging132.719 mph and coming within 50 seconds of finishing in less than three hours. In 2014 Brad Keselowski ran the fastest qualifying lap in 164.444 mph - true Monster Mile.