Boxing in Delaware

THE SWEET SCIENCE IN THE SHADOWS

A dark, moonless night, a clearing in the Pennsylvania woods just over the state line, scores of horse-drawn hacks tethered to trees. This was the typical setting for a boxing match in Delaware in the 1800s, when prizefighting for purses was proscribed by law.

Matches were arranged and financed by backers of the fighters, who would spread the word among local sportsmen. These “sports” were secreted to the venue in the middle of the night, where a ring was laid out with gas lamps in the corners. The gamblers cared little more for the combatants than they did for the dogs and cocks that fought to the death in gambling pits in back alleys and illegal houses throughout the region.

Many of these fights were similarly brutal. In 1876 Philip Costa, who fought around Delaware under the alias “William Walker,” was killed in a backwoods fight and the body dumped into the Delaware River by his seconds where it was discovered by fishermen. But the sports settled their bets.

Only fighting for a purse was outlawed. Delaware hotels and exhibition halls would stage “demonstrations of pugilism” for paying crowds between fighters who were each paid a fee, with nothing going to the winner. These exhibitions were little more than choreographed dance routines in the science of boxing. Often the two pugilists would travel together, pre-arranging the round when one or the other would go down, usually between the seventh and tenth.

The most celebrated case of illegal prizefighting in Delaware occurred on July 1, 1886 when three fighters, including noted heavyweight Sparrow Golden of Philadelphia, who was seconding for brother, were arrested on the Wilmington and Northern railroad pier. Authorities charged that tickets were being sold for $3 each and that the pugs battled for the lion’s share of a $100 purse. Local “sports” staged a benefit for the three men which attracted 400 supporters. Over 60 men testified at the trial, including several prominent Wilmington businessmen. The fighters were ultimately acquitted, but not before Sparrow Golden lost a thousand-dollar payday for a bout in England.

With the rise of the athletic clubs in Wilmington in the latter part of the century these exhibitions became more authentic tests of pugilistic skill. From these clubs emerged several popular fighters, including John “Midget” Glynn, a 110-pound featherweight with a rushing style, and lightweight Cornelius J. Moriarty, alias “Jack Daly.”

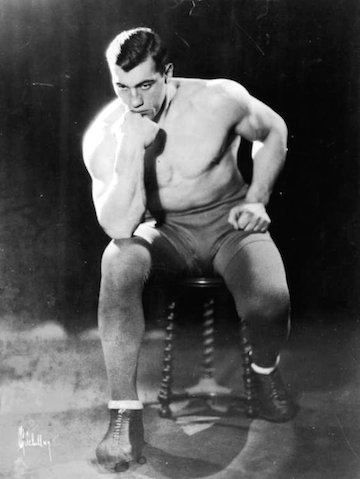

Lightweight Jack Daly was considered the finest Delaware boxer of the 19th century - willing and able to take on all comers up to heavyweights.

Both fought regularly on the undercards of nationally promoted fights. Daly, born and raised around 8th & Madison in Wilmington, was considered the greatest boxer ever developed in Delaware. He fought at 122 pounds but took on all comers, including even heavyweights. Daly won the Philadelphia Association tournament in February 1892 and a month later turned pro, winning his first fight at 125 pounds in four rounds against Ben Horn in Staunton, Virginia. Daly piled up over three dozen wins during the next decade. His greatest bout was against Englishman Stanton Abbott, who Daly fought to a draw after 37 rounds and 2 1/2 hours. The Wilmington man had much the better of the fracas but the referee called off the proceedings because “neither man was in any danger of being knocked out in less than 20 more rounds.” In 1898 he battered lightweight champion Kid Lavigne for 20 rounds in Cleveland but was robbed of the title when the bout was ruled a draw. It was rumored that the referee had his money on the champ.

While Daly and Glynn were well known in Delaware the boxers who were known across the country were the heavyweight champions, the first non-four-legged superstars in the sports world. John L. Sullivan, Bob Fitzsimmons and James Jeffries all fought exhibitions in Delaware. Thousands turned out to admire the champs’ physiques and skill with a punching bag. The three-round events were little more than sparring sessions but occasionally pugilistic exuberance could not be contained, as when Jeffries came to Wilmington. Reported one observer, “With a single exception the blows Jeffries administered were merely taps, designed to show how he can hit, but one poke, in the third round, was evidently more vigorous than the champion intended, and fairly lifted his partner from the floor.”

The best Delaware fight fans could hope for from appearances by champs like John L. Sullivan were tame exhibition matches when boxing was illegal in the state.

The last bare knuckle fight in Delaware was broken up by police in 1892 and concluded across the line in Landenberg. In 1901, after decades of legal and illegal boxing in the state, officials finally decided that all fighting was against Delaware law and stopped even exhibitions. The sweet science disappeared in the First State.

BOXING BECOMES LEGAL

In 1931, after an 18-year struggle, it became legal to stage a boxing match in Delaware for prize money. The first bill to allow prizefights was voted down 19-10 in the state legislature in 1913. Two years later the House passed a bill creating an Athletic Commission to sanction boxing bouts butthe movement went no further. From that point there was a boxing bill before the General Assembly nearly every year.

While the lawmakers wrangled, boxing was flourishing in Delaware. Boxing had been taught in the army in World War I and returning soldiers hungered for similar action in peacetime. Boxing fans in Wilmington could find bouts in the Pythian Castle at 908 West Street, in the Academy of Music at 10th & Delaware, at the Elam Athletic Club on Concord Pike, in the National Guard Armory at 10th & du Pont streets, and elsewhere. Every now and then law enforcement officials would raid a club and all the participants would be arrested. But there would be a good card next week somewhere.

The charades ended April 17, 1931 with the first boxing sanctioned by the state of Delaware at the Auditorium on 11th Street in Wilmington. The fighters were mostly bantamweights and lightweights who provided non-stop action for the 2003 people who paid their way in. Soon the first boxing club outside of Wilmington was being planned for the outskirts of Harrington.

Several months later big-name fighters began to appear in Delaware. The first was Primo Carnera, a massive heavyweight contender and possessor of the largest fist in boxing history. The 278-pound Carnera was matched against Armando De Carlos in the open air arena at Shellpot Park, a trolley park developed by the Wilmington City Railway Company in Brandywine Hundred in the 1880s. Tickets went for $2.10 and $3.50 - at the height of the Depression - and the gate was an enthusiastic 1700. Carnera, sporting an 85 1/2 pound weight advantage, bludgeoned De Carlos for four minutes and eight seconds until the fight was stopped. A more common card promoted local pugs and fight fans could see up to 30 rounds of action for 50 cents.

On his way to the heavyweight championship of the world Primo Carnera stopped in Wilmington to batter an overmatched opponent.

Before legalization Wilmington had been considered one of the “hottest” boxing towns in the East with packed houses at Shellpot Park and the Elsmere Fairgrounds. But after the game became legit the crowds dwindled. In the first year one boxing club was out of business and another punch drunk. Boxing had always been available in Maryland, Pennsylvania and New Jersey and the same fellows Delawareans had traipsed across the state line for years to see were being trotted out in Delaware with no originality, simply resuming tiresome grudges dating five years of more. The poor matches and boring mismatches were a lethal one-two to boxing in Delaware.

Route 13 became known as the “Graveyard of Boxing Hopes.” Clubs along the du Pont Highway like Shellpot Park, Playland and Harrington all went under. A grand new outdoor sports arena grandly called “Olympia” opened on the Causeway, six blocks from Front Street beyond Garausche’s Lane and Market Street in Wilmington. There was seating for 4200 but barely 1/3 of that showed on Olympia’s opening night and most of that crowd was papered. Olympia soon joined its predecessors on the canvas.

Having created this still-born sport the General Assembly tried to keep the game afloat. A proposal was made to allow bouts up to 20 rounds, which only three states permitted at that time. A compromise sliced the plan to a pair of 10-rounders each year. By 1938 there was enough boxing, bothamateur and pro, to support three outdoor summer clubs and plenty of fistic action was available for Delawareans.

These clubs and gyms began spawning fighters of some repute in the 1930s - Johnny Aiello, Al Tribuani, Lou Brooks - who could fill an arena but big paydays for promoters were rare. During World War II Delawareans were treated to exhibitions by such stars as Sugar Ray Robinson and Joe Louis but after the war the same old mismatches and tired promotions once again infected the boxing game in Wilmington.

When Freddie “Red” Cochrane, reigning world welterweight champion, stopped in Delaware during a barnstorming tour in 1945 and crunched a tomato can named Alex Doyle (New Jersey welterweight champion with a career 35-57-8 record)with a left hook in the second round the purists howled. In 1949 ex-middleweight champion Rocky Graziano, the biggest draw in boxing, came to Wilmington to battle a well-tenderized Bobby Claus (12-19-1). A turn-away crowd of 3910 at the old Auditorium was stunned to see Claus floor the Rock in the first round with a sucker punch but Graziano bounced up and pummeled the hapless journeyman.

RING Magazine, the Bible of boxing, pulled no punches with its harsh appraisal of the bout: “In digging up Claus, who had been knocked out 9 times in 18 previous starts, Graziano stretched the idea of safety a bit too far. It’s this sort (bad mismatches) that have kept Wilmington, Delaware from being one of the best fistic centers on the Atlantic Seaboard (remember that Red Cochrane-Midget Doyle whatsiz in 1945). Some folks never learn.”

By the next year, 1950, Claus and his trick knee had been knocked out so many times he was suspended in Pennsylvania. But he was still fighting in Delaware. In a comeback bout for native son Al Tribuani a paycheck named Manuel Rosa took a dive in the second round. When he was fined only $60 by the Delaware State Athletic Commission cynics said it was because it was such a bad dive.

Shenanigans like these were well on their way to killing boxing in Delaware when television shoveled dirt on the coffin. Since the 1950s live boxing has been a sporadic affair kept alive in the occasional card at Fournier Memorial Hall in Wilmington’s Little Italy section. To date Wilmington’s potential as a great boxing town has yet to be realized.

DELAWARE BOXERS

Johnny Aiello. Delaware’s first boxing hero of the legal age was Johnny Aiello, a former catcher at P.S. du Pont High School. Aiello was a 118-pound perpetual motion machine of a bantamweight. By 1938 the 20-year old had been boxing three years, losing only 3 of some 60 bouts. That year he won the Eastern Golden Gloves title and reached the finals of the national amateur tournament before losing.

Top amateur Johnny Aiello.

In 1940 Aiello, a Wilmington plumber, won the Golden Gloves again, this time in Madison Square Garden before 17,000 fans. Aiello, the veteran of more than 100 amateur bouts, turned professional but he was exposed as only a very good amateur fighter. In five months of professional ring work in 1941 as a featherweight he won seven times, lost twice and had one draw; he scored four knockouts. By 1942 he was retired in Wilmington, training aspiring boxers at St. Anthonys CYO before heading off to World War II in the U.S. Navy.

Lou Brooks. As a kid Lou Brooks did most of his fighting on the Wilmington streets. At Howard High School he was a fast halfback and track star before entering the ring. Brooks won his first amateur bout but the raw street-brawler lost his next six fights. The 175-pound Brooks observed and developed until his amateur career concluded in the 1941 Golden Gloves tournament which he won by battering his opponent through the ropes at one point.

Brooks won his first nine professional scraps, eight by knockout, when he was matched with Lee Savold at Wilmington Park. Savold was a bruising puncher who had once taken Joe Louis’ best blows. Newspaper accounts estimated the gate at over 8000, promoter Bob Carpenter claimed 10,000. Whatever, it was Delaware’s biggest boxing crowd ever and they saw one of the state’s best ever boxing shows. Brooks entered the ring a 3-1 underdog and weathered Savold’s bombs for five rounds, giving as good as he got. But in the 6th round the Wilmington light-heavyweight fell under the onslaught of Savold’s withering body punches.

Lou Brooks was the first Delawarean to make a mark in the upper weight classes.

Brooks ended his first year as a pro with a 14-1 record. In 1942 Brooks, a crowd-pleasing wild puncher, was a headliner at the major boxing clubs in Philadelphia. Fighting at his top weight ever, 185 pounds, his opponents included many ranking heavyweights and light-heavyweights. He battled twice with Joey Maxim, the #7 ranked light-heavyweight, drawing once and losing once. At the end of 1942 Brooks was the #13 ranked heavyweight by RING Magazine.

His career appeared to be on the rise when in 1943 Brooks was temporarily blinded by a wayward thumb from former light-heavyweight champion Melio Bettina in the first round of a bout in the outdoor arena in Philadelphia. The fight was stopped - and so was Brooks’ career. Four eye operations couldn’t restore full vision and after a few bouts in Mexico and Texas he retired. His largest purse had been $6900.

Brooks turned manager and instructor and in 1956 he was named the first black boxing judge on the Delaware Boxing Commission. He was the best big man to yet come out of Delaware.

Al Tribuani. Born in Philadelphia in 1920, Al Tribuani came to Wilmington with his family shortly afterwards and rose to the greatest prominence of any Delaware fighter before him. At Bayard Junior High School Tribuani played only soccer but longed for physical contact. He soon found himself in the downtown gyms under the guidance of his older brother Ralph, a former fighter turned trainer-promoter.

The sturdy 147-pounder found even more contact in the Salesianum backfield in 1937 and 1938 before transferring to Wilmington High School in 1939. Meanwhile Tribuani was piling up ring experience, taking over 150 amateur fights and losing only three. He capped an amateur career by winning the Eastern Golden Gloves welterweight title in Madison Square Garden on the same card as Johnny Aiello. Tribuani brought the crowd to its feet with two knockouts before decisioning Bobby Claus, a National Guard machine gunner from Buffalo, in an all-out slugfest in the final.

Tribuani, also a National Guardsman, turned pro as World War II was breaking out. His early bouts were carefully picked “stiffs” as he built a 15-2 pro record before winning a unanimous 10-round decision over former lightweight champion Lou Jenkins in front of 6500 Wilmington partisans labeled him as a potential contender.

In 1943 Tribuani earned a bout with Henry Armstrong, the only fighter ever to hold the featherweight, lightweight and welterweight titles at the same time. Armstrong, the first to inspire the proclamation “pound for pound the greatest fighter alive,” was attempting a comeback at the age of 30 after 17 months of retirement.

Al Tribuani was Delaware's best known fighter at md-century.

The match was made in the Philadelphia Convention Center and 12,633 fans were on hand, the largest crowd to ever see a Delaware pro. Armstrong entered the ring at 138 1/2 pounds while Tribuani tipped the scales at 146 1/4. The Wilmington fighter lost the 10-round decision as Armstrong was awarded seven rounds but the national media praised the great fight given by the “unknown.” Armstrong piped up, “It was a tough fight. I was fighting a superman.” The crowd had been so boisterous the fighters could not hear the bell at the end of the rounds.

Later that summer Tribuani fought twice against Al “Bummy” Davis in Philadelphia, in bouts that were classics of the era. Tribuani won both although in the rematch he exited the ring with a cheekbone fractured in three places. “Even now all I have to do to recall my toughest fight is rub my hand across the left side of my face. The pain and memory of that June night and a great fight against a real game guy flashes quickly to mind,” he remembered in 1953. For his part, Bummy Davis would die a few years later intervening in an armed robbery which sportswriter W.C. Heinz recounted in what is still considered the best sports profile ever written.

Within months Tribuani’s training had shifted from Wilmington gyms to boot camp at Fort Dix. In 1944 he was an infantryman in France. In the spring of 1945, only days before the war in Europe would end, Tribuani was struck by machine gun fire, shattering his left arm. He received the Bronze Star but never regained the snap in his left jab. He turned to training other fighters in 1947.

In 1949, after being absent from the square circle since 1944, Tribuani returned to fight an exhibition with welterweight champion Sugar Ray Robinson. As a gesture for his old Golden Gloves teammate Robinson came to Wilmington for only expense money. Tribuani trained for the four-round dance as if it was a real title shot but Robinson entered the ring at Wilmington Park with protective headgear and oversized gloves. The crowd booed but the champion wasn’t about to risk injury in this benefit.

Tribuani fought a few more times but his career was essentially over - just as were the glory days of Delaware boxing. The gate for the Tribuani-Robinson match was not nearly as large as promoter Bob Carpenter had expected and but a fraction of Tribuani’s bouts a decade earlier. The golden era of Delaware boxing passed with Al Tribuani.

Willie Roache. Willie Roache met more name fighters than anyone in Delaware history. Although “Whistling Willie” was born in Harrington he was not taken seriously as a boxer while in Delaware. The 130-pounder honed his skills in New York and New England as he became a challenger in the featherweight division. He would continue to box for more than two decades, eventually fighting for the world championship.

By his estimate Roache won more than 200 amateur fights in the 1930s before turning pro. His best year was in 1944 when he won 21 of 24 fights, including dropping the Mexican champion Ham Wiloby in the Blue Hen Arena at Third and Scotts streets in Wilmington. That year Roache also knocked down Willie Pep, one of boxing’s greatest little men, but ran out of steam in the 15-round match, his first go at the distance, and lost the bout. In December he lost the World Boxing Association’s featherweight championship to Sal Bartolo in the Boston Garden.

Roache also battled former lightweight champion Ike Williams in his 80-fight pro career, matches that took him across the world. His final record was only 30-47-3 but it was compiled against the best.

Henry Milligan. It was the type of story the media finds irresistible: Princeton graduate, Ivy League man, and professional engineer sullying himself in the boxing game. And the national scribes lined up. There were pieces in Sports Illustrated, the Los Angeles Times, the New York Times, even People Magazine. And Henry Milligan lived up to the hype.

Milligan was an all-around athlete at A.I. du Pont High School where he was a two-time state wrestling champion. At Princeton he was a 10-letter winner - a .300-hitting third baseman, a cornerback and punt returner and an All-America 190-pound wrestler. As impressive as this athletic resume was, however, there was nothing in the portfolio that was going to bring Milligan lasting recognition. And Henry Milligan wanted to be a famous person.

After graduating in 1981 he shrewdly decided to try his hand at boxing where he could indulge his passion for fitness and, if he was any good at all, would be sure to attract attention as an educated, white heavyweight. And Milligan proved to be amazingly good. After just seven months and twelve amateur fights - all knockouts - Milligan reached the semi-finals of the National Golden Gloves tournament.

At the Golden Gloves the 5’11”, 190-pound Milligan upset the number-one ranked Michael Arms before suffering a controversial loss in the semis. Conditioning was his forte, carrying him further than his limited natural fistic gifts could. Never did Milligan enter the ring thinking he was out-trained. By 1984 Henry Milligan was the national amateur heavyweight champion and a favorite to make the United States Olympic team. But at the Olympic Trials in Fort Worth, Texas Milligan was stopped in the second round by a little-known 17-year old slugger named Mike Tyson. His Olympic dreams shattered, Milligan announced his retirement from amateur boxing. His record of 41-6 included 31 knockouts, twenty in the first round.

Milligan expressed no interest in professional boxing but the lure of the spotlight had him back in the ring within a year. On March 20, 1985 he dropped Garland Hall at 1:55 of the first round to win his first professional fight in the Brandywine Club in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. He won his first eleven pro fights - again, all by knockout - before being stopped in the second round by Al Shofner at Delaware Park on May 10, 1986.

Later that year Milligan sustained bloody cuts over his eyes in a loss to Frank Minton and, still unmarked and hoping to remain so, he stepped out ofboxing.But once again the lure of celebrity enticed Milligan back. This time, in 1993 at the age of 35, Milligan won two comeback fight before suffering an 8th round knockout for the IBO Cruiserweight title. Afterwards, with a 15-2-1 pro record, he announced yet another retirement, having achieved his goal of lasting fame - certainly in Delaware.

THE PROMOTER

Raffaele Tribuani could have come straight out of central casting. He was born in the Republic of San Marino, a microstate on the Italian peninsula. The family came to Delaware when Ralph was still a kid. He was a teenage boxer and was on the undercard of the Primo Carnera heavyweight fight in Shellpot Park in 1931. The bout was canceled but the 17-year old Tribuani was enlisted as Carnera’s interpreter while he was in town.

Thus began a lifelong friendship and also a lifetime in the boxing game outside the ring for Tribuani. For the next four decades, until he died from brain surgery in the 1970s, Ralph Tribuani was at the center of most things boxing on the Delmarva Peninsula.

He promoted amateur boxing cards at Wilmington’s Auditorium and managed the career of his younger brother Al when he broke big. Tribuani handled the affairs of the fighters for the T & C Athletic Association, taking them to represent the city in national Golden Gloves tournaments in New York City and Chicago.

Tribuani was connected to all of the biggest boxers of the day and made matches for many of them to fight in Wilmington. After middleweight hero Rocky Graziano was suspended from fighting in New York in the wake of a bribery kerfuffle, Tribuani got him a license to fight in Delaware and revive his career.

Ralph Tribuani with middleweight champion Rocky Graziano. The Wilmington promoter helped restore Graziano’s boxng career after the boxer failed to report a bribe attempt.

As television eroded the interest in live boxing in the 1950s and 1960s Tribuani turned his talents to other endeavors - he promoted professional wrestling and put on rock-and-roll shows with such acts as Bill Haley and the Comets. He found work for old fighters as referees and was known to shovel money to local fighters and put on benefits to keep the fight game alive in Delaware. If Burt Young was doing homework on the inside game of boxing preparing for his role of Paulie in Rocky he could have done no better than tag along with Ralph Tribuani.

DAVE TIBERI

In 1898 Jack Daly was denied the opportunity to become Delaware’s first boxing world champion amidst a swirl of rumors that the referee was on the take. Nearly a hundred years later, as Dave Tiberi climbed out of an Atlantic City ring, Delaware still had not claimed a world champion and there were again dark rumors circulating about the integrity of boxing officials.

Dave Tiberi grew up at the back end of 14 children, including 12 boys. Six of the Tiberi brothers were involved in boxing, including Joe, who retired in 1984 with an 18-5-1 professional record. Dave turned pro in 1985 at the age of 18. Seven years later Tiberi had fashioned a solid record of 22-2-3 with seven knockouts. He was ranked as the #10 middleweight in the world by the International Boxing Federation and deserving of a title shot against champion James Toney of Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Toney entered the ring unbeaten in 28 fights, having knocked out 20 of his victims. He trained lightly for Tiberi and boasted that “he’s a good, average fighter, but he’s not in my league.” Tiberi, although having never been knocked down, had gone only ten rounds twice. Toney was a prohibitive favorite for the 12-round, nationally televised match.

The two fighters stood in the middle of the ring and traded punches throughout the fight. At the end of the first round Tiberi was staggered by a direct hit from a left hook but for most of the night the Delaware challenger initiated the action. The bigger punches were Toney’s, but Tiberi was the busier fighter. The final cards showed one judge favoring Tiberi 117-111 and two judges placing Toney ahead 115-111 and 115-112.

The split decision outraged the Taj Mahal crowd. A chorus of boos cascaded through the hall as Delaware fans carried Tiberi triumphantly from the ring. Commentator Alex Wallou, calling the fight for ABC television, incited the protests by terming it “the most disgusting decision I’ve ever seen.”

Donald Trump proclaimed the decision “an embarrassment to Atlantic City.” Delaware legislators pleaded Tiberi’s case in the federal government. The maelstrom of protest over the boxing “system” threatened to overshadow Tiberi’s gutty performance.

And it has been the last Tiberi boxing performance Delawareans have been able to see. Tiberi refused all lucrative offers for a rematch, insisting he would not face Toney unless he fought as champion and Toney as challenger. Standing on principle he retired to private life and community work back in Delaware.