Golf in Delaware

The First Tee

The first golf ball struck in Delaware was hit in the vacant fields south of Lancaster Pike on Clayton Street in Wilmington, near what is today Canby Park. It was the early 1890s and America’s first golf boom was underway. Golf clubs had started organizing only in the late 1880s but by 1900 there would be 982 courses across the country.

Lieutenant Governor J. Danforth Bush brought the first set of golf clubs into Delaware after a trip to Scotland. He laid out a rudimentary course to play the game. The greens of this primitive golfing field, it was reported, were “rough as an unpaved street, and the cups were made of empty tomato cans sunk into the ground.”

The activity out on Clayton Street attracted the attention of several members of the Delaware Field Club, organized in 1885 to play cricket. In 1894 these members started a course on their property in Elsmere, routing holes around houses and through cinder streets. Matches were soon arranged with neighboring clubs from Philadelphia and West Chester at the Field Club Course.

These golfing grounds were used until 1901 when the Field Club leased 147 acres of William du Pont’s estate on the Kennett Pike and incorporated the Wilmington Country Club. The initiation fee was the purchase of two shares of stock for $25 each. Annual dues were set at $12.

The new course was laid out by Henry Tatnall and J. Ernest Smith. The design was esteemed enough to host the 1913 United States Women’s Amateur Championship. No less an authority than Bobby Jones praised the 205-yard 6th hole as one of the finest of its kind when he visited.

Wilmington Country Club remained on the site for sixty years, weathering a conflagration of the clubhouse in 1924. Play began over two new courses designed by the two leading architects of the age - Robert Trent Jones and Dick Wilson - in the early 1960s. The South Course is regarded as one of the finest layouts in the land and has hosted several national championships.

Outside of Wilmington Country Club, golf was slow to take root in Delaware, however. Pioneer golfers were ridiculed as “big men chasing little white pills across the fields with big clubs.” Some men of means developed private courses at their estates but the next formal club was not formed in the state until the E.I du Pont de Nemours & Company decided to start a country club on property formerly occupied by the Wilmington Gun Club.

The original nine holes were completed in 1920, using dirt tees and sand greens. Golf was little more than a secondary activity at the new club. The most popular sport was baseball - especially women’s baseball - among company departments which had forged bitter diamond rivalries. By 1922 golf was popular enough to warrant the creation of a full 18-hole course and a large grey stone clubhouse, which was completed in 1924.

Early golf courses favored geometric shapes, like this rectangular sand green.

Wilfrid Reid, a Scottish professional who came to Delaware at the behest of the du Pont family, designed the DuPont Course. A second 18 holes was added in 1938 and a third course opened at Milford Crossroads in 1956. By 1965 the DuPont Country Club boasted four 18-hole courses and the largest private membership of any country club in the world.

The 1920s were the golden age of golf course design in the United States. After the initial boom golf actually faded for the first two decades of this century. By 1916 there were some 742 courses available - nearly 250 less than 1900. But by 1929 there would be 5,648. For more than ten years a new golf course opened on average every day.

Delaware was no different. Golf came to downstate; courses opened in Dover and Rehoboth. Newark established a course in 1922, with nine holes sculpted from a tract of 161 acres. Golf was now available in all of the major towns in Delaware.

THE EARLY DELAWARE PROS

In the formative years of American golf there was only one commandment for a club pro - Be Scottish. Americans believed that all Scots could play golf; it mattered little if he actually could. Many young Scots answered the call, sailing across the Atlantic to teach America golf, even if they had to learn the game along with their eager new disciples.

Wilmington Country Club, Delaware’s only club until 1920, was fortunate in its choice of early professionals - they could play a bit, too. First pro Thomas Clark was a good British player before signing on at the Kennett Pike club in 1903. His successor, Gilbert Nicholls, was one of the top tournament players in America. Born and weaned on golf in England, Nicholls came to the United States in 1897 at the age of 18. In 1902 he set an 18-hole scoring record in the U.S. Open. He was a two-time runner-up in the Open before settling in Wilmington in 1908.

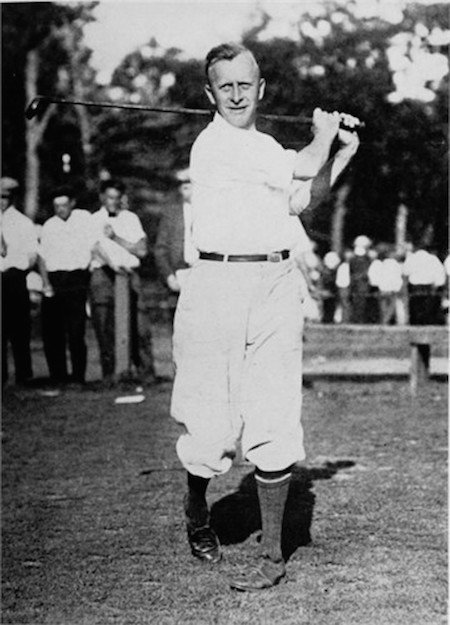

Englishman Gilbert Nicholls was a top American pro when he came to Wilmington Country Club.

The popular Nicholls was head pro at Wilmington for seven years, winning several national tournaments during his tenure, including the North and South Open in Pinehurst North Carolina that was just a notch below the U.S. Open in prestige in those days. In 1911 Nicholls set an all-time 72-hole scoring mark in capturing the Metropolitan Open with a 281, including an unheard of 66 in the final round. When Nicholls left Wilmington in 1914 he went to Great Neck Country Club on Long Island as the highest paid club pro in the country. He stayed 32 years until his retirement at the age of 69.

In turn, Nicholls was replaced by two more Brits, Wilfrid Reid and Alex Tait. Reid was a protege of golfing great Harry Vardon and compiled a fine competitive record, finishing as high as fourth in the U.S. Open in 1916 while at Wilmington Country Club. Never one to keep his golfing accomplishments under his hat it was said that his personal stationery was filled with so much detail of his golfing prowess that there was little room to write a message.

Wilfrid Reid finished fourth in the U.S. Open while pro at Wilmington CC; he designed over 50 courses, including work in Delaware.

Tait stayed as head man at Wilmington for 40 years, retiring in 1961 as Delaware’s last golfing link to ancient Scotland. Other Delaware clubs were similarly blessed with gifted golfers as pros in their early years. Tommy Fisher and Alec Douglas at DuPont Country Club and Rock Manor Golf Club, respectively, each stayed more than a quarter-century at their posts. At Newark Country Club head man Ed Ginther was talented enough to qualify for both the U.S. Open and the PGA.

One of the first great American-born club pros was Ed Dudley. Dudley was a Ryder Cup player when he came to Wilmington to take command of the Concord Country Club out at Painters Crossroads, then owned by Wilmington Country Club, in 1930. Dudley was a leader on the embryonic pro tour when northern club pros would travel across the South playing tournaments in the winter. On the 1931 tour, while representing Concord, Dudley led all golfers with a 71.39 scoring average, won the Los Angeles Open and the Western Open and made the Ryder Cup team again.

When Dudley left Concord in 1933 it was to return to his native Georgia for the best golf job in America - first head pro at Bobby Jones’ new Augusta National Golf Club. In 1964 Ed Dudley became the 35th enshrinee in the Golf Hall of Fame.

PUBLIC GOLF IN DELAWARE

On Labor Day 1921 a small golfing ground opened by Porter’s Reservoir on the north end of Wilmington. For the first time in Delaware golf could be played without belonging to a private club, by just paying a daily fee. Trolley cars brought golfers to the new Rock Manor course at the foot of McKees Hill.

A tent served as clubhouse. Experienced players were stationed around the nine holes to help newcomers. For a while play was actually free but a small fee was soon assessed to allow for course maintenance. So rapidly did the course grow in popularity that three years later Rock Manor was extended to a full 18 holes, and within another five years the course was stretched another 600 yards.

In a unique arrangement Rock Manor was owned by the city of Wilmington, administered by the Water Department and operated by the Municipal Golf and Tennis Association, a private club. Memberships were available but members could not claim preference in starting times over the daily fee player. In this way golf fees funded all construction and upkeep of the course. Rock Manor never cost Wilmington taxpayers one cent.

By 1929 nearly 30,000 rounds of golf were being played each year at Rock Manor, far more than any private course in the area. On many days more than 350 players teed off; the single day record reached 418. In 1937 Alex Findlay, a Scot living in Philadelphia who had played over 2400 courses, was hired to re-design the course with government WPA funds. Despite the Depression, Rock Manor became even more popular. “In season,” reported The Sunday Morning Star that year, “the weekly average of players totals 1500. Saturdays, Sundays and holidays find the course loaded.”

And no wonder. Rock Manor was the only public golf available to Delawareans for more than 40 years. In 1958 William du Pont Jr. donated land containing 15 holes of the old Wilmington Country Club to the city. The 108 acres were valued at more than $1,000,000, one of the greatest gifts ever given to the state for recreation. Du Pont later granted another 15 acres to insure a complete, re-designed 18-hole course at the site.

The new club was named Green Hill, a name linked to the property since 1846. The cost of a round on Delaware’s oldest golfing grounds was $2.50 during the week, $3.50 on the weekends. By 1970 more than 45,000 golfers a year were enjoying the historic links at Green Hill.

In the mid-1960s New Castle County officials prepared to build the first course by a local government in nearly 50 years. Only Rock Manor, mutilated by the new I-95 highway, and Green Hill were available to serve 343,000 county residents. The site chosen was on old state prison farm at Delcastle and when it opened in 1971 it became a showcase for public golf. The three-level, 190-car parking lot was built without removing a single tree. On the course, extra large tees, broad fairways and large greens conspired to manage the burden of heavy play smoothly.

Twenty years later the three courses still handled the bulk of public course play in Delaware. Several other semi-private courses opened to the public on a limited basis but south of Smyrna only one course, Old Landing Golf Course, welcomed the daily fee player. That changed dramtically as golf boomed again the 1990s. Southern Delaware positioned itself in the golf resort market and the First State ended the 20th century with more than two dozen course open for public play.

DELAWARE’S GOLF ARCHITECTS

Although some of golf’s most famous architects, most notably Robert Trent Jones and Jack Nicklaus, have stamped their imprint on Delaware, the state’s golfing grounds have been shaped to a remarkable degree by only two men.

Alfred Tull was born in England in 1897. His family emigrated to Canada ten years later and Tull came to this country at the age of 17. He began his career as a construction superintendent for Walter Travis, America’s first golfing champion, in 1921.

Tull first came to Delaware in 1929 to work with Devereaux Emmet on Henry du Pont’s personal course at Winterthur. Following Emmet’s death in 1935 Tull entered private practice as a course architect. His first commission was for nine holes on Lancaster Pike for the Hercules Company.

Tull became noted for his ability to lay out individual holes and establish a circuit by walking the land and staking the holes without consulting any topographical plans. In Delaware, he would go on to design the Nemours and DuPont courses at the Du Pont Country Club, the Brandywine Country Club, the Seaford Country Club and 18 more holes at Hercules.

Edmund Ault once estimated that he had designed or remodeled one-fourth of all the courses in the Maryland and Virginia suburbs around Washington, D.C. His percentage in Delaware is even greater.

A one-time scratch golfer, Ault was an engineer by training. After several seasons apprenticing in golf architecture he entered private practice in 1946 at the age of 38. In the early 1960s Ault introduced golf throughout downstate Delaware by building courses at the Dover Air Force Base, Dover Country Club, Sussex Pines, Shawnee and Garrisons Lake in Smyrna.

Recognized for his advocacy of flexibility in course design, Ault moved upstate in the 1970s. He re-routed Green Hill, now Porky Oliver, and created Delcastle and Pike Creek Valley (Three Little Bakers). When he was through Edmund Ault was responsible for 7 of every 10 holes of public golf in the state of Delaware.

THE PERSONAL COURSE

There are private courses and there are private courses. In the early days of Delaware golf several prominent men built small golf courses on their expansive estates. Henry Haskell and Charles Copeland laid out links at their homes of perhaps five holes. Pierre S. du Pont enjoyed golf on the grounds at Longwood.

But none matched the facilities set up by Henry F. du Pont. For decades du Pont enjoyed one of the world’s best personal courses. In 1928 du Pont commissioned Devereaux Emmet, one of America’s leading golf architects, to carve a golfing field from the rolling hills on his Winterthur estate. Emmet crafted an 18-hole course from ten greens and 17 tees. The full course played to 6480 yards; the front nine sporting steel markers, the home nine porcelain. Wide fairways reached 200 feet in some spots.

Like any other course, the Henry du Pont course employed a golf pro. Du Pont had met Percy Vickers in an indoor golf school in New York City and when the course was ready at Winterthur Vickers was on hand as pro and groundskeeper. Vickers, who would stay for more than thirty years, the course’s entire existence, ventured that, “There are no more than 10 golf courses in the country on the scale of Winterthur - I mean actually for golf and not a family playground.”

Henry du Pont would entertain 18-20 golf guests on a weekend. In his later years he confessed to being not particularly interested in scoring but in being outside for the exercise. He played every other day into his 80s, always walking and shunning a golf car. Vickers estimated that his boss would shoot in the 90s and du Pont was good enough to join the PGA Hole-In-One Club in 1941.

In 1963 du Pont’s personal course was converted into a private club, in part “to protect the Winterthur Museum from the inroads of residential building and traffic, and to add to the beautification of its contiguous gardens.” The members wanted to call their club “Winterthur” but du Pont considered that confusing and suggested the name “Bidermann” after the builder of the estate.

Delaware’s last personal course was not quite gone forever. Henry du Pont retained, in addition to his indoor driving range, three holes to play himself.

DAVE DOUGLAS

About the time Porky Oliver was building his game at Rock Manor another teenager was trading course records with him. Snowball’s rival was Dave Douglas, the son of Rock Manor professional Alec Douglas. In addition to their individual battles father and son teamed against Oliver and Wilmington Country Club pro Alex Tait in highly publicized matches.

Douglas, born in Philadelphia in 1918, stood 6’3” and weighed only 154 pounds. He lettered in basketball at P.S. du Pont High School. When Oliver, a sturdy 205 pounds, turned pro after high school he invited his old Rock Manor foe to partner in pro-am events. The “fat man and the thin man” made a formidable team, setting records in several tournaments.

The experience boosted Douglas’ confidence. He finished as low amateur in the Philadelphia Open and the Lake Placid Open and qualified for the National Amateur in 1938. That year the 20-year old Douglas turned professional by accepting the assistant pro job at Orchard Ridge Country Club in Fort Wayne, Indiana. He was back in Delaware by 1940 when he qualified for his first United States Open, shooting an 83-78 in the same tournament Oliver was disqualified for starting his final round early.

Douglas spent 18 months of World War II on board a hospital ship. The years after the war found him giving lessons at night at Wilmington’s first driving range, the Boulevard Driving Range at 40th & Governor Printz. By the end of 1947 Douglas was ready to try pro golf’s winter tour.

During a practice round at the Orlando Open, his third tournament, Douglas was playing with other unknowns Vic Catelino, Ellis Taylor, who would later win eight Delaware Amateur crowns, and Otto Greiner. Sam Snead, playing behind the young foursome, was hitting into them all day and when a second shot on a par five rolled between Catelino’s legs Vic suggested they allow the famous star to play through. “We will not,” said a proud Douglas. “He’s no better than we are.”

Dave Douglas (right) won eight PGA Tour titles but not a great deal of recognition. When he won his second tournament in San Antonio the local papers announced the he was “practically born and raised on his father’s Park Manor golf course in Delaware, Maryland.”

He proved it later in the week when he fired a final round 66 to join Jimmy Demaret and Herman Kaiser in a playoff for the $2000 top prize. Although Douglas had played before virtually no gallery to that point he cooly won the playoff the next day, first tying Demaret with a 71 and then winning the sudden death playoff on the first hole with a 5-foot birdie putt.

It was an impressive beginning but he struggled in anonymity on the Tour for the next 18 months. At the Texas Open in 1949 Douglas moved into contention with rounds of 65, 72 and 66 to earn a spot in the final threesome on Sunday with leader Snead. Douglas bogeyed the first hole but made seven birdies to finish with a 65 and his second title. The unknown underdog was hoisted to the shoulders of the crowd of 7000 and swept off the 18th green to the clubhouse. It took Douglas 15 minutes to travel the 100 feet from signing so many autographs. How unknown was Dave Douglas? San Antonio papers reported that he was “practically born and raised on his father’s Park Manor golf course in Delaware, Maryland.”

Douglas was one of the most likable and approachable players on tour. His tall frame and elongated swing produced a consistent fade on his long shots but his fellow pros admired most his stroke-saving short game. He finished 17th on the PGA money list in 1948 but several lean years had him contemplating quitting the tour by the start of the 1952 campaign.

He struggled through the winter tour with finishes of 27th, 33rd, 28th, 19th, 33rd and 26th and wasn’t nearly making expenses when he flashed to a win at Greensboro, worth $2000. He won the Ardmore Open in Oklahoma several months later, which carried one of golf’s top prizes - $5400. Playing as an unattached pro from Newark, Delaware, Douglas was the only player in field to break par for 72 holes. He finished the 1952 season as the 7th leading money winner with $15,173 and was named vice-president of the PGA by his fellow players.

His performance enabled Douglas to join Oliver on the 1953 Ryder Cup team. Remarkably, the two men who grew up on the Rock Manor links together twenty years earlier were now representing America in golf’s most prestigious international competition in Wentworth, England. Oliver and Douglas were paired in foursomes play and downed Peter Allis and Harry Weetman 2 and 1. Douglas tied in his singles match the next day as the United States brought the Ryder Cup home once again.

Always a streaky player Douglas began the 1954 season by not cashing a check for over two months before he won the $6200 top prize at the Houston Open and jumped to the top of the money list. He won only $6220 the rest of the year, however, and began searching in earnest for a club job. In 1956 Douglas accepted a post at the St. Louis Country Club. Where Oliver could never tame his wanderlust for life on the PGA Tour, returning time and time again from club jobs, Douglas settled into his work in the pro shop and was content to leave behind his touring days for good.

Like Oliver before him Douglas contracted cancer and, as his former partner did, returned to Delaware for his final days. Dave Douglas died in 1978 at the age of 60.

WITNESS TO HISTORY

In the 1950s Dave Douglas was twice witness to golfing history, attesting the scorecard for one of golf’s greatest rounds and one of the game’s most famous shots.

In 1951 United States Open Douglas trailed the leader Bobby Locke by a single stroke entering the 36-hole final day at Oakland Hills Golf Club in Birmingham, Michigan. Oakland Hills had recently been remodeled for the Open and players complained bitterly about its tight driving areas and heroic proportions. Douglas was paired for the last 36 holes with Ben Hogan who came off the pace to win the tournament with an astounding three-under par 67. It was only the fourth sub-par round of the week and two shots better than anyone managed that day. Many consider it the greatest round ever played in American competitive golf. Hogan himself admitted afterward that “I’m glad I brought this course, this monster, to its knees.” And Dave Douglas saw every shot.

If you walk up and down the practice range at any PGA Tour stop today and ask pros what tournament they most want to win you will hear “U.S. Open” or “Masters” or maybe “the Open Championship.” Jump into the wayback machine to the 1940s and 1950s, however, and ask the same question and you would just as likely hear “George S. May’s All-American.”

In an era when touring pros carpooled between tournaments, doubled up at cheap roadside motels and rarely played for first-place checks of more than $1,000 George S. May - the “S” stood for “Storr” but in golf circles it was considered “Sugar” - staged golf tournaments where the winner’s share was larger than any other event’s entire purse.

Win the Tam O’Shanter and a pro golfer was assured of finishing among the leading money winners for the entire year.

In 1953 the Tam O’Shanter was the first golf tournament to be televised nationally - with a single camera rigged behind the 18th green. The American Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), in its first year on the air, slotted one hour for the live telecast. Lew Worsham, whose previous claim to fame had been denying Sam Snead a never-to-be-won U.S. Open in a playoff at St. Louis Country Club in 1947, came to the 18th hole needing a birdie three to get into a playoff with Chandler Harper for the biggest first prize in the history of golf. With ten minutes left in the broadcast, the executives at ABC could not have asked for better sports drama.

Worsham drove the ball well and selected a MacGregor double service wedge to cover the remaining 104 yards. The ball soared above the Chicago River, slipped past two trees and landed on the front of the green about forty feet short of the pin. Jimmy Demaret, who was doing commentary on the radio, picks up the story: “The ball’s running toward the hole. Oh, I’ll be damned. It went in.”

“The Shot Heard Round The World” was worth $25,000 to Worsham. And just like that, ABC signed off from Niles, Illinois with the most dramatic finishing shot in professional golf history having been been witnessed on an estimated 646,000 television sets. And watching from the other side of the fairway was Worsham’s playing partner, Dave Douglas.

WOMEN’S PROFESSIONAL GOLF IN DELAWARE

The LPGA McDonald’s Championship was first served to area golf fans in the bucolic horse country of Chester County, Pennsylvania at White Manor Country Club in 1981. It was a superb golfing ground and organizers ran a first class event. The tournament quickly expanded into the richest payday on the women’s tour. In its first six years the McDonald’s Championship produced such quality champions as Jo Anne Carner, Beth Daniel, Patty Sheehan and Juli Inkster.

White Manor was rapidly losing its ability to nurture the exploding McDonald’s Championship. In 1986 the tournament committee went searching for a facility with two courses to accommodate the ever-expanding - and immensely profitable - pro-am portion of championship week. Prestigious Wilmington Country Club passed on overtures from the McDonald’s folks but they found a willing host across the Brandywine River at the DuPont Country Club.

The 41 1/2-acre site proved an ideal compromise. Worries about the venerable DuPont course’s ability to withstand the withering assault by the lady pros proved unfounded as the subpar round was the exception, not the rule. Betsy King won the first McDonald’s Kids Classic in Delaware with a six-under par 278 to claim the $75,000 first prize. She did it with a flair, birdieing three of the final four holes to pull away by two strokes.

The immaculately groomed layout won raves from the players. The next year, in 1988, 50 of the top 51 money winners came to Wilmington. Delawareans embraced the event as well and in 1989 a single-day LPGA tour record of 38,750 turned out for the final round. Over 2500 volunteers work on the event each year. The McDonald’s Kid Classic became a money machine for charity, generating two million dollars annually. More than $47,000,000 was raised for the McDonald’s charities, with a third staying in Delaware. The tournament was considered the largest fundraiser in the history of golfdom.

The success off the course was equalled by the play in between the ropes. The list of worthy champions lengthened - Betsy King, Akayo Okamoto and Sheehan and Daniel again. In 1994 the McDonald’s Championship graduated to become one of the major championships on the women’s tour.

In 1998 Se Ri Pak ignited a craze in South Korean women’s golf when she arrived in the United States as a 20-year old and won the McDonald’s LPGA Championship by three strokes with an 11-under par 273. A few months later she became the youngest winner ever of the U.S. Women’s Open.

Pak’s win began a run of Hall of Fame winners in the championship. Juli Inkster won the next two titles and Australian Karrie Webb captured the trophy in 2001.Pak won again at DuPont Country Club in 2002.

In 2003 Annika Sorenstam, the greatest female golfer of her generation, beat South Korean Grace Park on the first hole of a sudden-death playoff to win the fifth of her ten major titles. The next year in Wilmington she would win her seventh major championship.

That would also end the run of the tournament in Delaware. The next year the LPGA Championship moved to Bulle Rock in Maryland. Sorenstam won her third straight title but the tournament would never again find the same success after leaving DuPont Country Club.