1921-1930 courses

Pine Valley Golf Club (1921)

The two most famous residents of the New Jersey Pine Barrens, a swath of one million acres of scrub pines and sand in south-central New Jersey, go about their lives in near total secrecy. One is the Jersey Devil, a legendary winged creature with the head of a horse supported by a four-foot serpentine body. According to lore, the Devil appeared in the 1700s when an indigent woman named Mrs. Leeds was struggling to feed her 12 children in the darkest recesses of the Pine Barrens. Finding herself once again pregnant she is said to have exclaimed: “I want no more children! Let it be a devil.” The devil-child was born horribly deformed, crawled from the womb, up the chimney and into the woods where it was rumored to survive by feeding on small children and livestock. When a person saw the Devil it was an omen of disaster, particularly shipwrecks, to come. Sightings were common through the next two centuries and often breathlessly reported in the local newspapers. Once some local Pineys, as Pinelands residents are known, tried to claim a $10,000 reward for capturing the Devil by obtaining a kangaroo, painting stripes across its back and gluing large wings on the animal. But so far no documented Jersey Devils have been captured.

The other is Pine Valley Golf Club, which is seen by locals only slightly more often than the Jersey Devil. The club is notoriously private and releases no information. It maintains a national membership believed to be around 1000. Membership is by invitation, although the pathway to the first tee is unknown. Great wealth, however, will not buy one's way into Pine Valley. If not for a nasty habit of being ranked as America's best golf course by Golf Digest, as it was for 22 of the first 24 years of numbered rankings, it is likely the golfing world would know nothing of Pine Valley.

Pine Valley - here is the second hole - looked like no other golf course in America when it opened for play in 1921.

Pine Valley Golf Club is actually its own New Jersey borough, created in 1929. Only a Pine Valley member can own one of the 22 homes on the 620 or so acres of the club. There is a mayor and borough commissioners, a clerk, solicitor, tax assessor, tax collector and school district even though lessons learned on the golf course do not qualify as a school. Pine Valley even has a police force which takes turn accessing the squad car parked behind the gatehouse. The only road leading into the "town" is unmarked.

Pine Valley is located hard by the old Reading Railroad tracks that once shuttled tourists between Philadelphia and Atlantic City. Next door is Clementon Lake Amusement Park where generations of thrill-seekers rode the beloved Jack Rabbit roller coaster unaware that America's best golf course was just on the other side of the trees. But Pine Valley is not invisible to the public.

The club hosted the Walker Cup matches between amateur teams from the United States and the British Isles in 1936 and 1985 and footage of the course can viewed on YouTube from a match aired for Shell's Wonderful World of Golf between Byron Nelson and Gene Littler in 1962. And one day every year, usually a Sunday in late September, Pine Valley invites the public inside to view the final day of the Crump Cup, one of amateur golf's most prestigious events. Golf fans can not access the modest clubhouse but are free to roam across some of the most revered ground in golf. The tournament and the course are a legacy to the man whose vision created Pine Valley - George A. Crump.

Crump's grandfather sailed from Cheltenham, England in 1838 to work as an editor for the Philadelphia Inquirer. The next generation went became contractors and architects, and eventually hoteliers, owning expansive guests houses in Philadelphia and at the Jersey Shore. When he came of age as the curtain fell on the 19th century George Crump carried a calling card that identified him as being in the "Hotel Business."

The family business left plenty of time for diversion and Crump was an avid hunter. He also held memberships at four golf clubs around Philadelphia and another in Atlantic City. Crump was a member of a group of avid Philadelphia golfers who called themselves the "ballsomes" who often rode the train down to the ocean to play golf in the winter. During a round at Atlantic City Country Club in 1903 it was supposedly a Crump shot that landed close to the pin that led his foursome to coin the term "birdie."

Crump and his Philadelphia friends were good golfers but were continually bested in matches with their compatriots from New York and Boston. Among themselves they concluded their shortcoming was due to a lack of quality courses. Crump resolved to set out and build a world class golf course. His efforts were buoyed by the sale of the family's largest hotel in 1910, the Colonnade at 15th and Chestnut streets in downtown Philadelphia.

By this time Crump's young wife had died and he threw all his passions into his golf project. He traveled to Great Britain and Europe to study classic golf courses and returned to look for his dream piece of golfing ground. He supposedly saw it from the window of a train about 20 miles southeast of Philadelphia. Or he remembered it from past hunting trips. Or both. At any rate, Crump wound up buying 184 acres of Sumner Ireland's scrub pines in September 1912 for $50 an acre.

Crump pitched a tent and began spending his day wandering the property, dreaming of golf holes. The next spring he set about draining the swampland and brought in massive steam-powered winches to pull tree stumps out of the ground. They stopped counting at 22,000.

As work progressed, many of Crump's friends from the golf world stopped by to look over Pine Valley. On a tour of America Harry S. Colt, England's premier golf architect of the day, contributed a routing plan of the holes. Walter Travis, Charles Blair MacDonald, Donald Ross and A. W. Tillinghast all pronounced Pine Valley to be among the finest courses in the world even before if was finished.

Crump sent out a letter to prospective Pine Valley members and 141 responded affirmatively. One was Connie Mack, who was then in his 13th year of a 50-year run as owner and manager of the Philadelphia Athletics baseball club. In November of 1913 Crump and his friends played the first golf at Pine Valley over five completed holes. A year later eleven holes were ready, although Crump had expected the entire course to be completed.

George Crump spent his fortune on Pine Valley but never saw his vision realized in full form.

Work would slow even further in the years to come as Crump and his agronomists struggled to get grass to grow on the ancient sand dunes. By 1917 only 14 holes were completed. Crump has personally sunk $250,000 into Pine Valley which was now being referred to in some circles as "Crump's Folly."

In January of 1918 at the age of 46 George Arthur Trump put a gun to his head and pulled the trigger. He left no note. Holes 12-15 were still unfinished at Pine Valley. After recovering from the initial shock the Philadelphia golf community pulled together to finish Pine Valley and realize George Crump's dream. The turf issues were solved, architect Hugh Wilson of Merion fame oversaw the construction of the final four holes and a Crump brother-in-law wrestled the project's finances under control to "carry out the founder's wishes."

George Crump's main wish had been to create the sternest test of golf in America and that has been the result since the first full round was played in 1921. As the sign read that greeted those early golfers to Pine Valley: ABANDON HOPE ALL YE WHO ENTER HERE.

Latrobe Country Club (1921)

Latrobe is an old Pennsylvania Railroad town. It was laid out by a Pennsy civil engineer who named it for his old college classmate who was an engineer for the rival Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. They made steel and ceramics and mattresses in town. There was also a large brewery that would start to make Rolling Rock once the nation shed its Prohibition nonsense. By 1920 there was enough going on to form a nine-hole country club.

On the crew to build the Latrobe Country Club nine was a 16-year old local boy named Milford Deacon Palmer. In 1926 he was hired as the course greenskeeper and when the Depression came the club could not afford both a professional and a superintendent so in 1933 they gave Deke both jobs. By that time Deke was married with a family and to keep his energetic three-year old son Arnold busy he handed him a sawed-off woman’s mashie and a golf ball and told him to “hit it hard, boy.”

Young Arnold wasn’t allowed to play the Latrobe course except in the early mornings or late evenings when members weren’t around. He started toting bags at the age of 11 and squeezed in enough golf to win five straight club caddy championships, five West Penn Amateur titles and the Pennsylvania State High School Championship twice before pacing his bags for Wake Forest University.

He started to win tournaments at the national level but after a stint in the Coast Guard Palmer took a job with W.C. Wehner Company in Cleveland, selling paint. Golf professionals were still often not permitted in their own clubhouse as Palmer saw with his father at Latrobe and he was not in a hurry to pursue that life. But after unexpectedly winning the 1954 U.S. Amateur at the Country Club of Detroit he took the professional plunge.

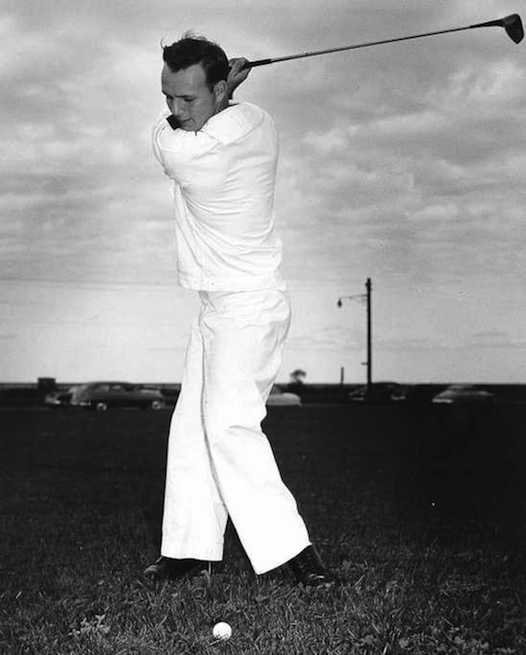

After leaving Latrobe Arnold Palmer signed on with the Coast Guard but he did not spend all his time on the water.

His firs professional win came at the Canadian Open in 1955 and four wins in 1957 insured he was not going to be a club pro anytime soon. Masters championships in 1958 and 1960 made him a star and when he drove the first green in the final round of the U.S. Open at Cherry Hills to jumpstart a round of 65 and a come-from-behind two-stroke win Arnold Palmer’s position as the most popular player in golf was secured.

In the 1960s Latrobe Country Club purchased additional land and Deke and Arnold Palmer set out to build a full eighteen holes; it was one of the first of over 300 the King would design. Construction began in 1963 and in 1971 Arnold bought the place. If members thought that the biggest name in golf might transform their club they did not know their hometown hero.

Palmer infused Latrobe with some genuine Pennsylvania tradition by adding covered bridges - the state has more than any other state - across creeks that could be used for storm shelters. After Deacon Palmer died in 1976 his son directed that a red pine being removed was carved into a life size figure of his father as a tribute. As a Pennzoil pitchman Palmer starred with an old tractor on which his father taught him to drive - the tractor remains on sit in a warehouse and is often trotted out for display at outings.

Latrobe has always been a private club but after Palmer and Marriott hotels built a SpringHill Suites hotel up Arnold Palmer Drive a ways guests were permitted to book a tee time. At last members of “Arnie’s Army” could off a salute on the leader’s own course.

Shady Rest (1921)

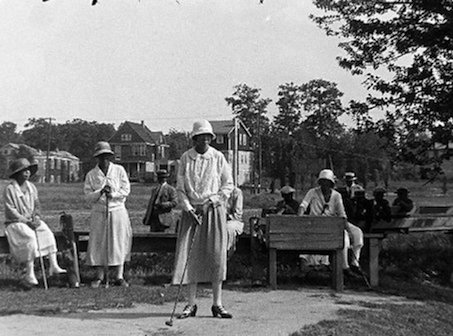

There were a few African-American owned and operated golf courses in the United States before Shady Rest but the black investors who comprised the Progressive Realty Company created the first-ever full-fledged African-American country club when they purchased the old Westfield Golf Club in 1921. Westfield was created in 1900 on the 18th century farm that Ephraim Tucker built with the help of $680 paid for his service in the Continental Army during the American Revolution. The clapboard Tucker farmhouse, after doing duty as a tavern, was converted into a clubhouse.

Shady Rest members enjoyed all the amenities of country club life with horseback riding, tennis, fine dining, ballroom dancing and, of course, golf. Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughn from nearby Newark all performed at Shady Rest during the Roaring Twenties. In 1957 Althea Gibson, the first African-American to win a Grand Slam tennis title, played an exhibition before 800 fans on the at Shady Rest one month after winning Wimbledon and a few weeks before capturing the U.S. Open. In the early 1960s she would become the first black player to compete on the LPGA Tour.

In 1931 John Shippen came to Scotch Plains to serve as greenskeeper and club professional at Shady Rest in 1931. John Matthew Shippen, Jr. was born in Washington D.C. in 1879 to an African American Presbyterian minister and a Shinnecock Indian mother. When Johns was nine years old his father was sent back to serve on his mother’s reservation on eastern Long Island. When Shinnecock Hills Golf Club opened a few years later found work in the caddy yard and on the maintenance crew. He also learned the game from Shinnecock pro Willie Dunn.

John Shippen was the first African-American golfer to tee it up in the United States Open.

When the second United States Open came to Shinneock Hills in 1896 Shippen and a Shinnecock Indian friend named Oscar Bunn entered. Many of the Scottish and English players in the field threatened to withdraw if the two unknown players of color competed but Theodore Havemeyer, first president of the United States Golf Association, would hear nothing of it.

Playing with 1895 U.S. Amateur champion Charles Blair MacDonald, the 17-year old Shippen got around in 78 strokes to share the opening round lead at his home course. He faded to a tie for fifth place after recording a disastrous 11 on the par-four 13th hole to finish with a 159 total for the 36-hole event. When John Shippen collected a $10 prize he was not only the first African-American to play in the Open but the first American-born professional.

Shippen became a teacher and club repairman at Shinnecock Hills. During the summer of 1897 he gave lessons to financier J.P Morgan who progressed enough to belt long drives which satisfied him enough to quit the game. Shippen played in four additional U.S. Opens, finishing as high as fifth in 1902 at Garden City Golf Club. He taught at Spring Lake Golf Club in New Jersey, Maidstone Golf Club in New York and Aronimink Golf Club in Pennsylvania.

Waiting to tee off on a busy day at Shady Rest.

After arriving at Shady Rest Shippen stayed for the next three decades. In 1938 Scotch Plains Township acquired Shady Rest after the Great Depression scuttled the Progressive Realty Company. In 1964 Shippen retired and the same year the township took over operations, opened the course to the public and renamed it Scotch Hills Country Club. The 2,247 yard course, playing to a par of 33 is still open to the public.

Baltustrol Lower and Upper Courses (1922)

For Louis Keller it was all about money. But before that it was about rubbing shoulders with the rich and famous.

Keller was born into a well-to-do Manhattan family in 1857, the son of a lawyer who was the first United States Commissioner of Patents. But not as well-to-do as young Louis would have liked. Worse the family home home on Madison Avenue was close enough to the city’s luxurious mansions that he could press his nose against the outside window panes. As a young man he was disinclined to work for a living and attempted to live the life of a gentleman farmer on a family farm in New Jersey. When that didn’t work he drifted into gunsmithing and other jobs without success.

If he could not be a member of New York’s elite Keller figured the next best thing would be to live vicariously through the lives of wealthy socialites by writing about them in a newspaper. His gossip rag provided him a living but it led to a more profitable idea - The Social Register. Keller printed up lists of members of New York Society - selected only by him - and then sold subscriptions to the lists, one in summer and one in winter, to those on the lists. Keller was soon publishing his Social Register in cities across America.

Meanwhile, there was that family farm in Springfield, New Jersey sitting idle. How could he turn it into a money-maker. In the 1890s he noticed that many of his Social Register clients were playing golf. So he found an Englishman named George Hunter who had heard of the game to build him a nine-hole golf course in 1895. The little course was well-received but Hunter never undertook such work again.

Keller had no intentions of playing the game himself. His plan was to hit up Social Register subscribers for memberships with dues of $10 per year. Keller did not even plan on belonging to the club - he was going to lease the course and an old barn that had been renovated into a clubhouse back tot he members. His role, in addition to landlord, would be as Secretary, or general manager. Final decisions about the goings-on of this golf club would rest with the Board of Directors.

The Baltustrol caddie yard, circa 1914.

For a name, Keller chose “Baltustrol” which sounds as if it escaped from a verdant Scottish glen but is nothing of the sort. Baltus Roll was a thrifty woodchopper who once made his living on the mountain that contained Keller’s farm. Rumors percolated that the backwoods Midas kept a treasure in his house and one night a pair of highwaymen decided to fin d out for themselves. They dragged Roll from his house but he apparently never revealed the hiding place of any gold as the life was choked out of him. After that grisly incident things around Springfield began being named for Baltus Roll.

Keller knew that one of the best ways to build his young membership was with big tournaments and so he made sure Baltustrol Golf Club was in the second wave of 14 clubs that joined the original five USGA members. Baltustrol was a founding member of the influential Metropolitan Golf Association around New York City and the New Jersey State Golf Association. The course was buffed up to 18 holes in 1898 and between 1901 and 1904 hosted a U.S. Women’s Amateur, a U.S. Open and a U.S. Amateur.

In 1903 Keller brought George Low, a 29-year old professional from the cradle of golf in Carnoustie, Scotland, to Baltustrol. In addition to his job in the shop Low was given free hand to massage the golf course as he saw fit. He also had time to launch a bustling trade in club-making, maintaining a golf shop in New York City until the 1930s. Baltustrol was host to the 1915 U.S. Open and the course again won good words in the wake of amateur Jerome Travers’ triumph.

Keller’s business-like approach to golf club management paid off handsomely. The membership rolls swelled to more than 700, including 600 golfing members. Baltustrol was considered the largest club in America and after the 1915 Open Keller began scouting around for an architect to build a second course in addition to the Old Course. He talked with A.W. Tillinghast and Tillie said, yes, he could do that but he had a better, if more audacious, idea - plow up the existing course and build two new courses of equal quality. Not a championship course and a gentler test for members.

In 1918 the club approved plans for Tillinghast’s “Dual Courses.” Two full-length championship courses built together? Golf construction on such a scale had never been attempted before. And it would take four years for the project to be completed. Unfortunately Keller fell ill and died of an intestinal disorder in February 1922, four months before the courses, named Upper and Lower, were officially open. In his last act of service to Baltustrol he directed in his will that all debts he held for the club be released.

Both the Upper and Lower courses at Baltustrol have hosted numerous major championships. There have been many great champions, including Phil Mickelson and Jack Nicklaus, who won two U.S. Opens on the Lower Course. But no one ever battled Baltustrol like Mickey Wright.

Amateur Jerome Travers won the 1915 U.S. Open at Baltustrol and never entered the tournament again.

Mary Kathryn Wright was born in San Diego in 1935 and discovered golf at the age of nine. Two years later she broke 100 for the first time and her picture appeared in the local paper with the prescient caption, “The Next Babe (Didrickson Zaharias)?” She won the Southern California Girls’ Junior title at the age of 14 and the started working with Los Angeles teaching pro Harry Pressler, molding the swing Ben Hogan would call “the best he had ever seen.”

After spending a year at Stanford University to please her father, Wright departed for the women’s professional tour, then only five years old. In 1958 she won her first U.S. Women’s Open and would win at least one major title in each of the next six years. Wright was often vexed by a balky putter and the U.S. Open at Baltustrol’s Lower Course in 1961 was one of those times, leading to a second round 80.

In those days “Open Saturday” called for players to finish with 36 holes and at the Lower Course, which included holes from the men’s tees, that meant a lot of long iron and fairway wood approach shots into the greens. In the morning round Wright made five birdies to shoot a 69 and turn a four-stroke deficit into a two stroke lead. After lunch she hit sixteen greens in regulation, two-putted every hole, and posted a 72 for a six-stroke win. The New York Times minced no words about the performance, “Miss Wright’s 72, 80, 69, 72 was five over par for the championship course. Her 69 was one of the best scores in the history of the tourney, considering the length of the course, and one of the best ever credited to a woman golfer in the United States.”

Wright was just hitting her stride. From 1961 until 1964 she won 44 times, the most of any professional golfer in a four-year span. She wrapped up the run with her fourth U.S. Open win in front of her home fans at the San Diego Country Club. Five years later, foot problems forced her out of the game at the age of 34. At Golf House, the headquarters and museum maintained by the United States Golf Association in Far Hills, New Jersey - not far from Baltustrol - there are special rooms dedicated to four players - Bobby Jones, Ben Hogan, Arnold Palmer and Mickey Wright.

Cherry Hills Country Club (1922)

Golf eras are fractured like a perfectly cleaved diamond. Bobby Jones never competed against Ben Hogan. Jack Nicklaus never competed against Tiger Woods. But on one Saturday in 1960 in the Front Range of the Colorado Rockies the eras of golf collided with three legends - one certified, one in his own time and one future - all having a chance to win the sport’s biggest prize.

Cherry Hills golf course was as unlikely setting for such a drama. If a U.S. Open club could be called “plucky,” it would have been Cherry Hills. Cherry Hills was not the reigning club in Denver. That honor belonged to the exclusive Denver Country Club that had been founded in 1887 and built its first golf course in Overland Park in 1894. Two years later the DCC was the first club west of the Mississippi River to be admitted to the United States Golf Association.

Cherry Hills was started in 1922 by a bunch of wealthy Denver Country Club members who hired William Flynn to design a golf course after meeting him at a DCC luncheon. Flynn was a product of Merion and Pine Valley and he injected the Cherry Hills property with touches of both with imaginative short holes and devious interrupted fairways. He made meticulous drawings of each hole on graph paper which were framed and hung in the club card room. One thing Flynn learned in Philadelphia was how to price his services - he hit up the deep-pocketed Cherry Hills founders for $4,500 for their chance meeting with an experienced architect from back East.

Those pockets shrunk considerably during the Great Depression but what is golfing heaven for if not to encourage a club to exceed its grasp? Cherry Hills went after a United States Open but was stonewalled by the USGA which demanded a $10,000 guarantee to hold its champions west of that darn Mississippi for the first time. Protesting that there had never been a guarantee before Will Nicholson, the Cherry Hills representative, stammered, “Ten thousand dollars” Hell, we don’t have enough in our treasury to buy a case of ketchup.”

The club had in fact managed into its second decade only because members backed a large mortgage with personal assets dodge foreclosure. But Nicholson knocked on enough doors in Denver to raise the ransom and U.S. Open arrived in 1938. Ralph Guldahl, a self-taught Texan who had quit golf a few years earlier to sell cars, defended his 1937 title to become one of only six players to win back-to-back United States Open. Guldahl would make the World Golf Hall of Fame but was always known on Tour for his habit of combing his hair on the course, a ploy he said steadied his nerves.

The Eastern golfing establishment learned there was golf played west of Chicago and Cherry Hills pocketed $23,000 in much needed gate receipts. But the most enduring headlines to emerge from the 1938 U.S. Open came courtesy of Ray Ainsley, a club pro from Ojai, California. Ainsley’s approach into the tricky 397-yard 16th tumbled into the brook bordering the green. Ainsley later claimed he though he had to play the ball as it lay, there not being much water in the Topatopa Mountains and all. So he slashed at the ball bobbing in the current. And again. And again. And again, as a crowd formed to watch, excitedly pointing out the ball as it got lost in the energetic waters.

Official scorer Red Anderson convulsed in laughter and lost track of the swings. Playing partner Bud McKinney couldn’t keep count as well. Eventually Ainsley was credited with a 19 but the actual score could have been as high as 23. Either way it set a record for the highest score on a single hole in a U.S. Open. A little girl in the joyous gallery turned to her mother and said, Mummy, it must be dead now because the man has quit hitting it.” As they say, some stories are too good to check.

At the next U.S. Open at Cherry Hills the story would be so good they wrote books about it. In 1960 Arnold Palmer flew into Denver as the hottest player in golf having already won the Masters and four other tournaments. Palmer struggled on the Flynn layout and was unable to break par in any of the first three rounds. After 54 holes he trailed leader Mike Souchak by seven shots; worse, he trailed another dozen players as well.

Palmer began his final round by driving the 346-yard first green to set up a two-putt birdie. He holed a 90-foot chip on the second hole and had six birdies by the time he reached the eight tee. He reached the clubhouse in 65, the lowest final score ever shot in a U.S. Open. Back out on the course 48-year old four-time U.S. Open champion Ben Hogan was paired with 20-year old amateur Jack Nicklaus.

After an eagle on the 540-yard 5th and a birdie at the 438-yard 9th Nicklaus surged into the lead as he made the turn. Three-putt bogies at 13 and 14 derailed his chances on the back nine, leaving him to finish second - the first of 19 runner-up finishes in a major the Golden Bear would endure. Hogan was tied for the lead on the 17th tee, a 544-yard par five. After two expertly placed shots the Hawk watched glumly as his approach shot caught a ridge on the green and spun back down into the water and made bogey. He drowned another ball on the 18th trying a risky line to get the tying birdie. Arnold Palmer had made the greatest comeback in U.S. Open history which would his only win in the national championship. He left Cherry Hills truly the King of golf. But it was left for Ben Hogan to put a bow on the 1960 U.S. Open. “"I just played with a kid who if he had a brain in his head should have won this thing by 10 shots,” he said.

Nicklaus and Palmer would return to Cherry Hills many times. In 1993 Nicklaus did get his win by nipping fellow Ohio State Buckeye Tom Weiskopf by a stroke to win the U.S. Senior Open with an ominous thunderstorm spitting over the mountains. Palmer was invited back in an official capacity with his design partner Ed Seay to add some snarl to Flynn’s course in preparation for the 1978 U.S. Open. One of the things Palmer did was push the build a new tee on the first hole to stretch it to 404 yards. There would not be another plague placed on the brick wall around the tee box next to his anytime soon.

Winged Foot - East and West Courses (1923)

It is not unusual to hear members at event venues with more than one course deflect praise for the tournament track and say something like, “You should really play our other course. It’s harder.” That is almost never true unless that is a Winged Foot member. While the West Course tends to get the bulk of major championship play those tournaments can be switched to the East Course and you would not hear a peep from the competitors or purists. The courses are that interchangeable.

Winged Foot was built as the playground for members of the New York Athletic Club who told A.W. Tillinghast to “give us a man-sized course.” He gave them two, although it was not choice land. Tillinghast recruited a platoon of 220 local farmers to blast away 7,200 tons of rock and remove 7,800 trees. The West is longer and get tabbed for men’s championships. The East has more water and doglegs that can be challenged and, to hear many tell it, trickier greens. It hosts major women’s and senior championships. Each carries a USGA slope of 141.

If it wasn’t for meteorological intervention just before the 1929 U.S. Open it may be the East Course that gets all the rapturous publicity and not the West. The East Course was designed by Tillinghast to be longer and was scheduled to host Winged Foot’s first major. But it got beat up during a severe storm and the event was switched to the West Course. Players quickly learned not to get above the pin on the Winged Foot greens that tend to slope from back to front but Bobby Jones was still stranded 12 feet above the hole on the 72nd hole needing a make to tie Al Espinosa in the clubhouse. He coaxed the left-to-right breaker into the cup and won a 36-hole playoff the next day by 23 strokes. Generations of golfers since have tried to duplicate that putt with little success.

Al Espinosa watched Bobby Jones make a wickedly difficult putt on the 72nd hole to tie him for the 1929 U.S. Open - and then lost by 23 strokes in the playoff. Espinosa did win the first four Mexican Opens after the tournament began in 1944.

Winged Foot is the ultimate players club both in the pro shop and in the locker room. Head professionals Craig Wood and Claude Harmon each won a Masters while taking time off from the Winged Foot golf shop. Wood also added a U.S. Open title. Assistant pros Jackie Burke Jr. and Dave Marr would graduate into major winners. On Tour and later in the television tower Marr would always remind people that, “Winged Foot (West) has the eighteen best finishing holes in golf.”

Winged Foot member Tommy Armour returned three major championship trophies to the Tudor-styled fieldstone clubhouse between 1927 and 1931. Not that any of these players would ever be guaranteed a walkover in a match at Winged Foot where 40 or 50 members carry a handicap index under 2 at any given time.

One of those members who did need strokes on the first tee was David Bernard Mulligan. Born in Pembroke, Ontario in 1871, the youngest of seven children, the precocious Mulligan passed the Canadian Bar at the age of 17 but favored the hospitality business instead. Over the next 40 years he managed the Waldorf Astoria and owned the Windsor Hotel in Montreal. Mulligan played his golf at the Country Club of Montreal and usually provided transportation for his foursome in his Maxwell-Briscoe roadster. There was a bone-rattling roadway on the Queen Victoria Jubilee Bridge just at the club entrance and with his hands numb from gripping the steering wheel his buddies often Mulligan the liberty of a “correction shot” on the first tee.

In 1937 Mulligan came to the United States to take over the Biltmore Hotel next to Grand Central Terminal and became a member at Winged Foot. One day he hit one long and wide off the first tee and instinctively reached into his pocket to hit another. Hi explained to his puzzled playing partners his Canadian custom. When they asked him what he called the shot, in a flash, he said, “A Mulligan.”

And so the quintessential player’s club, host to seven men and women’s U.S. Opens, is also home to the handicapper’s helper.

Congressional Country Club - Blue Course (1924)

You have to pity Congressmen. Most of their time is spent begging for money. All of those days wasted traveling around to meet Wall Street bankers, captains of industry and deep-pocketed special interest groups. Wouldn’t it be much more efficient if all the lawmakers and influence peddlers had one place where they could all gather and socialize out of the glare of the public eye? Say a private country club for instance? And just so there will be no doubt who the pleasure palace retreat is for we’ll name it Congressional.

How will that fly?

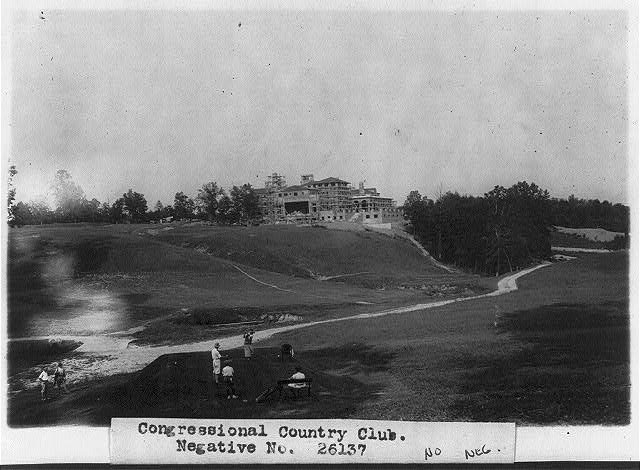

In 1921 it got off the ground awfully fast. The pilots were a pair of Republican representatives from Indiana named Oscar - Bland and Luhring. The Grand Old Party controlled both the House of Representatives and the Senate and Republican Warren Harding was just settling into the White House. Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover was gangbusters for the idea and signed on as the first club president.

Play went on at Congressional as America's largest clubhouse was being readied.

But Congressional was a bi-partisan effort from the get-go. Former President Woodrow Wilson was handed an honorary membership. And inclusive. William H. Taft, who taken another job after his Presidency as chief justice of the Supreme Court, was also given an honorary membership so all three branches of the federal government were represented. To make sure the government folk always had a stimulating game with the people they represented Bland and Luring sold $1,000 life memberships to the Rockefellers, duPonts, Harrimans, Chryslers, Carnegies and Hearsts of the world.

Devereux Emmet was recruited to transform a rolling patch of 406 acres in Bethesda, Maryland into a golf course. Lt. Colonel Clarence O. Sherrill of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was on hand to make sure everything went smoothly with the construction crew. More tax payer money went to the Marine Band that entertained at the grand opening on May 23, 1924 for a select group of 7,000 well-wishers. Lest anyone worry that the Washington crowd would not be socially lubricated during Prohibition the invitations included a BYOB.

Sometimes in Washington you get so gung-ho over an idea you forget you have to pay for it. That was the case with Congressional which operated with no real budget. Almost immediately there were financial woes and in 1940 the club’s assets were put up for public auction. Congressional was spared a future as a suburban housing development by, surprise, the federal government. During World War II William “Wild Bill” Donavan commandeered the club to train spies for his clandestine Office of Strategic Services. Learning how to infiltrate the 140,000 square foot Spanish Revival clubhouse - America’s largest - led to the creation of the CIA.

With the $307,000 rent payment and restoration fee from Uncle Sam banked Congressional emerged from World War II as a member’s club with an emphasis on championship golf and not ethics-challenged political deals. Robert Trent Jones arrived in 1957 to build nine new holes and makeover nine of Emmet’s original holes to create the Blue Course. Twenty years later George and Tom Fazio would do the same with the other nine to form the Gold Course.

The Blue Course hosted the 1959 United States Womens Amateur won by 24-year old Curtis Cupper Barbara McIntire. Five years later Jones’ brawny course would be the longest ever - at 7,053 yards - U.S. Open course. Tommy Jacobs, who had been the youngest player to compete in the Masters when he was 17 years old in 1952, nonetheless tied the Open scoring record with a 64 in the second round to storm to a three-stroke lead over first round leader Arnold Palmer.

To start the final 36 holes on Saturday Ken Venturi fired a 30 on the front nine to pull within two strokes of Jacobs after the third round. It was a rare burst of form from Venturi whose career had ebbed to a low point after three near-misses at the Masters in recent years and a car accident in 1961. Venturi banked only $3,848 in 1963 and had not even been invited to the Masters a few months earlier.

The heat in Washington that had shut down the nation’s capital in the summers before air conditioning was roasting the Blue Course with temperatures over 100 degrees. Venturi was acutely affected and a club member Dr. John Everett, accompanied him on the afternoon round, providing wet towels and salt tablets. A marshal walked along with an umbrella to shield Venturi from the sun. He would lose eight pounds on the day. When Venturi holed his final putt to secure a four-stroke win with an even par 70 his playing partner, 21-year old Raymond Floyd, plucked the ball out of the hole for him.

In the U.S. Open in 1965 at Bellerive Venturi missed the cut by 11 strokes. He had surgery on both hands and won his last Tour event on his childhood course at Harding Park in 1966. Venturi went on to become one of golf’s most popular television announcers. Congressional has continued hosting U.S. Opens as well with popular champions Ernie Els winning in 1997 and Rory McIlroy setting scoring records in 2011. But one thing would not continue after Congressional in 1964 - no longer would the U.S. Open be a test of both skill AND stamina. After that there would be no more 36-hole final day Saturdays.

And about the visionaries who put the wheels for Congressional Country Club in motion, Oscar Bland and Oscar Luhring? The voters threw them both out of office in their re-election bids in 1922.

Harding Park Golf Course (1925)

In 1924 Scottish architect Willie Watson showed up at Merced in the City by the Bay to build some some golf courses. He started by designing two courses on the south side of the lake for the Olympic Club and then he drew up plans for a course on the north side that was named for Warren Gamaliel Harding, the 29th President of the United States who had died in office of a cerebral hemorrhage two years before while in San Francisco while on a speaking tour.

The Olympic Club is a notoriously private group that flashes into the news every decade or so when it hosts a major championship, particularly the U.S. Open in 1955 when unheralded club pro from Iowa named Jack Fleck beat Ben Hogan by three strokes in a playoff and in 1966 when Arnold Palmer squandered a seven-stroke lead on the final nine holes of the U.S. Open and lost a playoff to Billy Casper. But Harding Park, a public course frequented by a seemingly endless string of outstanding golfers, was almost always making headlines.

Watson and his contractor Sam Whiting, who would sign on as superintendent at the Olympic Club for thirty years, routed the course through avenues of soaring Monterey Cypress trees, tucking the first nine holes inside the circling home nine. For novice players they included a nine-hole Fleming Course that played to a par 30. Their design fee was $300. From the time Harding Park opened it was hailed as the finest municipal golf complex in the land.

Ken Venturi won three San Francisco City Championships at Harding Park.

The San Francisco City Championship was a fixture at Harding Park and often produced golf as fine as any in the country. In 1956 two-time champion Ken Venturi, who played his first founds at Harding, met defending San Francisco and United States Amateur champion Harvie Ward in the finals. An estimated 10,000 fans turned out to see Venturi win his third city title 5 and 4.

Future major winners George Archer and Juli Inkster would also capture San Francisco City Championships. Other major winners Bob Rosburg and Johnny Miller did not but they played plenty of rounds at Harding, where Miller claimed he learned how to putt. All the pros showed up at Harding Park in 1944 for the Victory Open and in the 1960s the Lucky International Open sponsored by the Lucky Lager Brewing Company was a Tour fixture. If great courses beget great champions, consider that six major winners won the eight PGA events at Harding Park: Gary Player, Gene Littler, Jackie Burke, Jr., Archer, Venturi (his last of 14 PGA wins) and Billy Casper.

Deteriorating conditions at Harding forced to PGA to leave and the shabby facilities were not much better for the locals. One San Francisco City Championship was contested with 17 temporary greens, white circles painted into weed-choked fairways. For Sandy Tatum, one-time USGA president and veteran of 40 San Francisco City Opens, the deterioration was too much to bear.

Tatum began a serpentine and oft-times torturous crusade to bring the PGA Tour back to Harding Park. A fifteen-month renovation ended with the WGC-American Express Championship in 2005, with Tiger Woods outlasting John Daly in a playoff. In 2009 Harding Park became the first public course to host the Presidents Cup, downing the International Team 19 1/2 to 14 1/2 behind Woods’ 5-0 mark in the competition. On the horizon in 2020 is the PGA Championship.

When Daly was told about the rich history at Harding Park and how the course had reached its nadir in 1998 when it was used to park cars for the neighboring U.S. Open at the Olympic Club Long John replied, “What they should have done was play the Open here and park the cars at Olympic.”

Tam O’Shanter Country Club (1925)

If you walk up and down the practice range at any PGA Tour stop today and ask pros what tournament they most want to win you will hear “U.S. Open” or “Masters” or maybe “the Open championship.” Jump into the wayback machine to the 1940s and 1950s, however, and ask the same question and you would just as likely hear “George S. May’s All-American.”

In an era when touring pros carpooled between tournaments, doubled up at cheap roadside motels and rarely played for first-place checks of more than $1,000 George S. May - the “S” stood for “Storr” but in golf circles it was considered “Sugar” - staged golf tournaments where the winner’s share was larger than any other event’s entire purse.

May was an Illinois farmboy who took his degree from the Illinois State Teacher College and hit the revival tent circuit selling Bibles in the days before World War I. In the 1920s he transformed himself into an “efficiency expert,” what is better known as a management consultant these days. His first client was the forerunner of the Sunbeam Corporation which had just released its first household appliance called the Princess Electric Iron. May thrived pitching his advice to small and medium businesses and in 1929 added offices in New York and San Francisco to supplement his Chicago client list.

May’s consultancy business weathered the Great Depression and when the clubhouse of his course, Tam O’Shanter Country Club, burned in April 1936 and bankrupted the owners he stepped in and bought 84% of the stock. A minority owner in the New York Yankees would one day say of the managing partner of the Bronx Bombers, "There is nothing in life quite so limited as being a limited partner of George Steinbrenner.” That is how the 80 other members who held the remainder of Tam O’Shanter, designed by Charles Dudley Wagstaff in 1925, would soon feel in May’s wake.

Many private clubs around the country folded during the economic hard times of the 1930s and May was going to make sure that Tam O’Shanter, where he had been a member since its founding, was going to be run like a business not subject to the whims of the members’ bank balances. He poured $500,000 into rebuilding a sprawling Prairie-Style concrete-and-glass clubhouse with thirteen bars sprinkled across its three tiers. In case prospective members could not locate Tam O’Shanter they could find it with a 100-foot high water tank shaped like a white golf ball perched on a crimson red tee.

George May's Prairie-style clubhouse rose from the ashes of the original in the 1930s.

On the golf course May set greenkeeper Ray Didler to work raising tees, reworking greens and taming the north branch of the Chicago River that crossed seven holes and had a nasty habit of flooding in the spring. For the convenience of members he installed telephones on every tee. By 1941 May was ready to begin staging national golf tournaments.

George S. May invented the modern golf tournament at Tam O’Shanter, treating golf as a spectator viewing experience for the first time. He built the first grandstands on a golf course. May put up golf’s first leaderboards on the course, keeping the results fresh with scores called in by a platoon of workers armed with short-wave radio devices. He sold hot dogs and beer and set up outdoor pavilions; fans were also free to go in the clubhouse and try their luck at Tam O’Shanter’s slot machines if they so wished.

May printed programs with player information and also wanted players to wear identifying numbers on the course. When some players like Ben Hogan balked at the notion, May added bonus money to the checks of those who complied. Eventually a solution was worked out so that the caddies wore the numbers, not the players.

May visited the U.S. Open in 1940 and was appalled at the $3.30 ticket price. He charged just one dollar and over 20,000 fans a day would come through the Tam O’Shanter gates. Of course, he was able to make up the revenue with sales of programs, refreshments and a cut of the gambling receipts as the game was spread to the masses.

George S. May was golf's greatest showman from his home at Tam O'Shanter.

And there were those life-changing purses. Byron Nelson, whose swing was so pure the USGA mimicked it to create its equipment testing machine dubbed “Iron Byron,” was one golfer with his eye always on the prize. Nelson maintained he would play pro golf only until he had enough money to buy a ranch back in Texas. He won four of the first five Tam O’Shanter Opens and so much prize money the players called the event the “Byron Nelson Benefit.” After winning a record 18 tournaments in 1945 Nelson had enough money for that ranch and left competitive golf the next year at the age of 34.

May’s tournaments looked different from other professional events between the gallery ropes as well. If he was going to stage an All-American Open that would include all Americans and he would often have as many as 20 African-Americans in his fields. And he put on professional tournaments for women with large purses before there was an LPGA.

In 1953 May was out of the office one day when a call came in from the fledgling American Broadcasting Company (ABC) that had just gone on the air that year and was considering televising the world’s most expensive golf tournament. The Tam O’Shanter World Championship was offering a $25,000 first prize; Ben Hogan pocketed $9,500 for winning the U.S. Open, the Open Championship and the Masters that year. And that did not include the contract for a series of 25 one-day exhibitions at $1,000 a pop.

The network offered to put the Tam O’Shanter tournament on the national airwaves if May paid $32,000. An assistant in the office, Chet Posson, took the call. May was gone but ABC needed an answer with the tournament only ten days away. Without authorization, Posson agreed. When May fount out, he exploded - he would have paid a million dollars for the exposure.

For the world’s first nationally televised golf tournament a single camera was rigged atop the grandstand behind the eighteenth green. ABC slotted one hour for the live telecast. Lew Worsham, whose previous claim to fame had been denying Sam Snead a never-to-be-won U.S. Open in a playoff at St. Louis Country Club in 1947, came to the 18th hole needing a birdie three to get into a playoff with Chandler Harper for the biggest first prize in the history of golf. With ten minutes left in the broadcast, the executives at ABC could not have asked for better sports drama.

Standing on the tee, Worsham had bad memories of a back nine 42 on the final day at Tam O’Shanter that cost him golf’s biggest payday. Worsham drove the ball well and selected a MacGregor double service wedge to cover the remaining 104 yards. The ball soared above the Chicago River, slipped past two trees and landed on the front of the green about forty feet short of the pin. Jimmy Demaret, who was doing commentary on the radio, picks up the story: “The ball’s running toward the hole. Oh, I’ll be damned. It went in.” Oops.

And just like that, ABC signed off from Niles, Illinois with the most dramatic finishing shot in professional golf history having been been witnessed on an estimated 646,000 television sets. The next year the U.S. Open was on television and the Masters started broadcasting in 1956. Golf on television has been a staple ever since but only once - when Isao Aoki dunked a 128-yard wedge on the final hole of the 1983 Hawaiian Open have television viewers watched a PGA Tour event end with an eagle from the fairway.

May seized his moment after the triumph of the 1953 Tam O’Shanter World Championship and immediately announcing onthe 18th green that next year’s event would have double the purse - $50,000 and 50 exhibitions. Twenty-eight year old Bob Toski won the tournament and after his exhibition contract was fulfilled he left the Tour to spend time with his family and became one of the game’s most visible teachers, appearing in some of golf’s earliest instruction videos.

It would be television that would bring Tour players the kind of money they once only expected from George May. And those expanded purses would erode tolerance for the Tam O’Shanter tournaments that Life magazine once termed “an 18-ring circus” and the Satuday Evening Post called “a cross between a county fair a good airplane crash.” For all of May’s positive contributions to professional tournament there were others that were not as well-received. There were the clowns he hired to work the galleries during the tournament, the golfer he paid to wear a costume and compete as the “Masked Marvel” and the picnics that spectators were encouraged to spread out along the fairways.

In 1958, feeling unappreciated, May stopped putting on tournaments after holding 34 tournaments offering $2 million in prize money in 17 years. At Tam O’Shanter he erected a sign stating that everyone was welcome, except PGA pros. But George May was not through sending tremors throughout the golf world. For the 1960 golf season at Tam O’Shanter May replaced caddies with golf cars. Reaction from the hidebound world of golf was swift.

When George May looked into golf's future he saw motorized cars.

Joesph Dey, the Executive Director of the USGA said, “Tam O'Shanter must have its reasons, but this can't be done at all clubs. First, some courses are too hilly. Second, there are 6,000 golf courses. Half of them are public where most players can't afford carts. Third, the rules of golf recognize the caddie as a human being and permit a player to consult with him.”

Harold Sargent, President of the PGA, chimed in, “I don't understand why Tam O'Shanter did it. I'd hate to see this done everywhere. We give boys employment in a good environment. It's an antidote to juvenile delinquency and a source of supply of future golfers. Furthermore, this would be harmful to golf courses like ours that are not built for carts.”

Bill Adkins, a Palm Desert, California golf pro, kept his progressive stripes well hidden when he said, “I don’t like it. Golf is a game, not a commercial operation.” For two decades George May had been trying to prove that golf was a business and those inside the sport were still not paying attention. But May would only have to suffer such fools for two more years. He died in 1962 from a heart attack at the age of 71.

Tam O’Shanter died along with him - almost. The course was sold in 1966 and the property almost immediately developed. But the Niles Park District saved a slice to open a 2,250-yard nine-hole course in 1970 that included parts of the original first hole and the old 16th remains intact as the third hole. The historic 18th hole is no more although the park encourages golfers to “walk the very spot where Lew Worsham holed out a wedge from 104 yards to win the 1953 World Championship of Golf over Chandler Harper, by one shot!”

The Course at Yale (1926)

In the first half of the 20th century most of the best American golfers played their way out of caddie yards. Lately junior golf programs and colleges have been the breeding grounds of top players. In 1961 an underclassman from Ohio State named Jack Nicklaus became the first winner of the NCAA Championship who would later win a professional major championship. Ben Crenshaw won three consecutive NCAA titles at the University of Texas in the early 1970s and Phil Mickelson matched his record as an Arizona State Sun Devil. The only year Mickelson did not capture the championship was as a junior and he could console himself with having been the second college student to ever win a PGA Tour when he birdied the 72nd hole to win the Northern Telecom Open in Tucson. Scott Verplank had been the first when the Oklahoma State Cowboy bested the play-for-money crowd at the 1985 Western Open.

The first American collegiate golf course was laid out on the Princeton University campus in 1895; now named the Springdale Golf Club it is still in use. In March of 1897 representatives from Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Columbia and Pennsylvania met to form the Intercollegiate Golf Association, although “all colleges of America” were invited to send six-man teams and players to compete for the cups on offer. The group accepted an offer from the Ardsley Casino Golf Association on the Hudson River to stage its first tournament two months later.

Players arrived at a private railroad depot to take on the course of Jay Gould, J.P Morgan and William Rockefeller that was called the “finest and longest in the world” by Willie Dunn when he laid it out two years before. Louis P. Bayard, Princeton ’98, battled the Ardsley links for 91 strokes to take home the individual cup. In 1904 Chandler Egan, just months removed from Harvard University, became the first college graduate to win the U.S. Amateur.

Chandler Egan was the first college graduate to be a national champion.

Yale won the first team championship. The Yale Golf Club had been organized in 1896 with the encouragement of freshman John Reid, Jr. whose father organized the “Apple Tree Gang” of St. Andrew’s. Yale continued to dominate early collegiate golf, winning 13 team championships and nine individual titles -including Reid in 1898 - before World War I intervened.

The Yalies honed their game on local New Haven courses but players and alumni were regularly agitating for a university-only facility. The opportunity came in 1926. Sarah Rey Tompkins, whose husband Ray had captained Yale national champion football teams in 1882 and 1883, donated a 720-acre estate known as Marvelwood to the university in the name of her late husband. The former home of John M.Griest who had made New Haven the world’s foremost manufacturer of sewing machine attachments, was turned over to Charles Blair Macdonald who passed the project onto Seth Raynor.

Raynor was like no other architect working in American golf in the first decade of the 20th century. He was not Scottish and there is no indication he ever traveled there or even toured noted courses in the United States. He played golf but did not love the sport. Raynor came at golf architecture from a civil engineering background, only leaving the profession to shape Macdonald’s masterpiece at the National Golf Links at the age of 34 in 1908.

After about 1915 Macdonald stopped actively designing golf courses and left the architectural details to Raynor, only occasionally dropping in an opinion in an advisory role, as he did at Yale. As was his wont, Raynor moved more earth than any other golf course builder and there was plenty of earth to move on the sprawling Griest Estate that was infested with rocks. The construction tab rose to $400,000 - the most expensive course built to that time.

Raynor’s genius was in always converting those massive piles of moved dirt into eye-pleasing natural configurations. His architectural sensibilities came straight from Macdonald, who trafficked in recreating the classic holes of Europe. At Yale the standardbearer is the par-three 9th hole which has been praised as the “best inland par three in America.” It features a carry over Griest Pond from an elevated perch into a green sixty five yards deep with a five-foot swale across its mid-section, emblematic of the Biarritz hole at Pau, France.

The Course at Yale is considered the best campus golf course in America and Raynor’s finest achievement among some 100 golf courses, many of which like Fishers Island and the Camargo Club, are highly regarded. Unfortunately it was also the pinnacle of his career as he died moths later at the age of 51, leaving many projects on the drawing table, including the preliminary routing for Cypress Point Golf Club on the Monterey Peninsula.

The Yalies continued to have success on the golf course, winning four more team titles in the 1930s. After the NCAA formed in 1939 Yale won one more time in 1943 to bring its record-holding title of collegiate team championships to 21. Oddly, while the Golf Course at Yale holds many collegiate tournaments it has never been tapped for the NCAA Division I Men's Golf Championships.

Oak Hill Country Club - East Course (1926)

In 1921 the University of Rochester came knocking on the door with a wild offer. We know you like your little club here, they said, but we really, really want your site on the banks of the Genessee River. Give it to us and we’ll give you 355 acres of farm land we’ve got over in Pittsford. And then they opened a few briefcases filled with George Eastman’s Kodak money.

The Oak Hill members had started their club with nine holes back in 1901 and added nine more holes on their 85 acres in 1910. The club was thriving, everyone was happy. Why would they just give all that up?

It took three years to hash out the details of the land swap. Oak Hill got four times as much land and the university tossed in $360,000 to ease the relocation pains - enough money to build two golf courses and a Tudor-style clubhouse that would be the envy of any English baronial estate. And they could keep playing on the old course until the new club was ready. The University of Rochester got a new River Campus that helped transform the institution from small liberal arts college to an influential research pioneer.

Donald Ross got the job of designing the two golf courses and truth be told the club did not trade for prime golfing ground. The turf was pretty well worn out after a century of farming. Ross had now qualms about the barren land - it was what he was used to from his youth growing up on Scottish seaside links. He routed two courses through the property that was pinched in the middle concentrating on small, elevated greens and providing for multiple possibilities of attack.

When the members saw Ross’ work they appreciated his thoughtful design but the place looked, well, lacking in joy. What it needed was one or two or 75,000 trees - Dr. John R. Williams, a pioneer in the use of insulin in charge of the project - stopped counting after awhile. So Oak Hill grew up as a hybrid of sorts; there were Donald Ross’s esteemed green complexes but his intended approach angles were narrowed to whatever the new forest permitted.

But it worked. After the USGA came for the first time in 1949 with the U.S. Amateur, executive director Joe Dey asked club officials, “Where have you been for 20 years?” In the coming years there would rarely be more than five years without a major golf event at Oak Hill.

When the U.S. Open arrived in 1956 Cary Middlecoff won the last of his three major championships. He followed his father and two uncles into dentistry and was commissioned into the United States Army in world War II as a dentist. He filled 12,093 teeth during his 18-month hitch but found enough time to practice his putting that he became the first amateur to win the North and South Open in Pinehurst.

After leaving the Army Middlecoff joined his father’s practice but in 1947 he turned professional at the age of 26. For the next ten years his nameplate stayed on the office door as he won 40 PGA tournaments. The doctor never filled another tooth.

Lee Trevino was another military man who joined the tour late, at age 27. But when he came to Oak Hill for the U.S. Open in 1968 that was about all he had in common with Dr. Cary Middlecoff. Trevino never knew his father and was raised in Dallas by his mother and grandfather in a house with no electricity or running water. He was picking Texas cotton at the age of five and learned golf in caddie yards and a par-three course where he hustled bets playing with a taped-up Dr. Pepper bottle.

Whereas Middlecoff already claimed three dozen titles before teeing it up at Oak Hill Trevino was in his second year on the Tour and had yet to win. He would also be playing a slightly different course. Robert Trent Jones, a Rochester native who claimed he learned to love golf architecture as a young man watching Ross create Oak Hill, was brought in to toughen the course in 1957. He had his sons at the 1956 Open measuring drives so he could best plan the course’s new defenses.

Although he had won Rookie of the Year in 1967 after he shot 69 in the opening round on the East Course Trevino sat in a golf cart enjoying a post-round beer and no one came by to say anything to him. The same happened the next day after a 68.

But after he continued with two more 69s to become the first player in U.S. Open history to post four rounds in the sixties, everyone knew Lee Trevino’s name. Finishing second was another player whose first-ever PGA win was a U.S. Open - Jack Nicklaus. The Golden Bear would finish second to Trevino in four of his six major wins.

Nicklaus would extract a measure of revenge at Oak Hill in 1980. In a year when Trevino won the Vardon Trophy for low stroke average Nicklaus ravaged the East Course in six-under par to win the PGA Championship by a then-record seven strokes. Nicklaus was the only player in the championship to finish under par. That is not surprising as only ten players have ever finished 72 holes at Oak Hill’s East Course under par in five major stroke play events.

Nicklaus was also playing a different course in 1980 than he had seen in 1968, besides the oaks growing for another dozen years. George and Tom Fazio came to Rochester in 1979 with more than a little touch-up on the agenda. They replaced four of the original Ross holes which raised some hackles but no one seemed to cast aside the long-held reverence for Oak Hill East, no matter how different it looked since Donald Ross got on the train to return to North Carolina.

Dr. Williams’ trees and Ross’s landforms come together to form a unique memorial along the 13th hole - the Hill of Fame. Beginning in 1956 Williams began the tradition of honoring “persons of character” in the game of golf by affixing plaques to trees on the hill. To date 42 men and women have been so honored.

Riviera Country Club (1927)

Hollywood stars are used to doors swinging open for them wherever they go. That was certainly not the case at Los Angles Country Club that had started in 1897 amidst the oil wells and dusty cattle pastures. The LACC treated movie people like box office poison after the studios started to make films on the old Wilcox ranch at Hollywood and Vine in 1910.

With the Q scores of both Hollywood and golf on the rise in the 1920s the celebrity elite needed a place to play. Some went to Bel-Air and others signed on for memberships at Riviera. Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford led the march to Riviera, which was started in 1925 by the Los Angeles Athletic Club. Spencer Tracy, Humphrey Bogart, and Clark Gable landed at Bel-Air. As for the LACC, the members never did cotton to movie folk. Bing Crosby bought a house on the course but was still rejected for membership. Cowboy hero Randolph Scott became a member only after he quit acting for the oil business.

George C. Thomas Jr. designed both Bel-Air and Riviera - and the north Course at Los Angeles Country Club, which the USGA often laments as the best course in America never to hold the U.S. Open. Thomas was the son of a wealthy Philadelphia banker who possessed a marked affinity for creating beauty, as befits a man who hybridized 40 roses in his lifetime and authored several books on the breeding and care of cultivars. He also raised English setter dogs and won Best of Breed at the Westminster Kennel Club in 1901 and 1903. Thomas also knew his way around a golf course, playing to a two handicap at times, with scores often dipping into the 60s.

Thomas dabbled with golf course design with a nine-holer in Marion, Massachusetts in 1904 and then laid out his first 18 holes on the family estate in suburban Philadelphia that would eventually become Whitemarsh Country Club. His first outside commission came in 1910 in Spring Lake, New Jersey where Thomas learned the beauty of bunkering from George Duncan, restorer of several important holes at Royal Dornich in Scotland. Thomas took no fee for his work, his last on the East Coast.

Early action on the 6th green.

During World War I he served as a captain in the United States Army, reportedly having outfitted his unit with his own money. On his Army application in 1917, when he was 43 years old, Thomas listed his profession as “Executor-Trustee-Author.” He was an expert aviator who survived three major crashes at the European front.

Thomas moved to California after the war and revived his interest in golf course design. At Riviera, Thomas was dealt the worst golfing ground in his Southern California experience. He balked at taking the job after seeing the barren Santa Monica canyon and only agreed if Billy Bell was made Construction Supervisor. The duo were able to make magic in the arroyos as Alister Mackenzie was moved to remark upon visiting Riviera that Thomas’ design was “as nearly perfect as any I have seen.” The earth shaping came at a steep price - at $243,827.63 Riviera was one of the most expensive courses in the world.

One of the most unique touches Thomas gave Riviera was a bunker in the middle of green at the par-three 6th, tilting the putting surface to still afford players on the wrong side an opportunity to two-putt. Thomas reasoned that if the bunker was more annoyance than challenge it could always be filled in. The bunker is still there and in a twelve-year stretch of keeping records during the Los Angeles Open from 2003 until 2014 the pros recorded 19 four-putts and one five-putt on the hole.

Thomas hit the inaugural tee shot at Riviera on June 24, 1927 and then, having designed twelve courses, authored the recognized masterpiece Golf Architecture in America: Its Strategy and Construction and drifted back to horticulture before dying in 1933.

In an effort to stave off mudslides in 1934 kikuyu grass, a hardy, drought-resistant turf native to East Africa, was planted on the hillsides. The verdant grass became synonymous with Riviera as it was planted in the fairways (where it gives golfers plump, spongy lies), the rough (where it can be tamed by only the strongest of wrists) and the green collars (where loss of control of the club at impact is a very real possibility).

The Los Angeles Open started in 1926 and Riviera quickly joined to rotation of courses as host; since 1973 the event has been held almost exclusively at Riviera. The L.A. Open was a true “open” - anyone who qualified could play in the tournament. that meant African-American Bill Spiller in 1945 when the Los Angeles Open was the only regular tour stop not to exclude minorities. Spiller, who missed the cut, hardly made news that year at Riviera since Babe Didrickson Zaharias was also in the field.

Mildred Didrickson grew up in Beaumont, Texas excelling at every sport she tried. She first came to national attention in the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics where as a 21-year old she won gold medals in the 80-meter hurdles, the javelin throw and the high jump. Sportswriter Grantland Rice suggested that she take up golf and three years later she was playing in the Los Angeles Open, when all you needed to do to play was fill out an application form.

Shortly after discovering golf Babe Didrickson became one of the greatest players ever.

Didrickson missed the cut at the Griffith Park course shooting 84-81 but she was likely distracted by her playing partner, a professional wrestler named George Zaharias - the “Crying Greek from Cripple Creek.” The couple married before the year was out.

Zaharias stuck with golf and began winning women’s professional tournaments - she would win 48 and ten considered “majors” in her career - while setting her sights on a return to the Los Angeles Open. She missed qualifying in 1944 but shot 76-76 the next year at Baldwin Hills, another George Thomas course, to make the field for the big tournament. And she had played from the men’s tees.

Unlike 1935 Babe’s appearance was not treated as a sideshow. She was paired with Ed Furgol, a future U.S. Open winner from Utica, New York who played with a permanently bent left elbow that was the souvenir of a childhood playground accident, and Ivan Sicks. Zaharias opened with a 76 and made the 36-hole cut but missed the 54-hole cut that was in effect at that time and failed to cash a PGA check. Babe Didrickson Zaharias would be the last woman to play on the men’s PGA tour until Annika Sorenstam teed it up at Colonial Invitational in 2003, where she also missed the cut.

In 1948 Riviera became the first course west of the Rocky Mountains to host a U.S. Open. Hogan won by three with a record total of 278 for his thrid win at Riviera in 18 months. In 1950, less than a year after a near-fatal car accident Hogan tied Sam Snead after 72 holes before succumbing in an 18-hole playoff.

The next year Hogan’s comeback was dramatized by Hollywood in Follow The Sun with Glenn Ford in the lead role. Snead and Cary Middlecoff and Jimmy Demaret appear in the movie but not Hogan. But Hogan did work with Ford, an enthusiastic golfer, before shooting began and he was on set at Riviera calling for retakes when the actor’s form did not meet his standards.

Riviera has taken several other star turns for nearby Hollywood. Katherine Hepburn, who was a member who preferred playing from the white tees, filmed Pat and Mike with Spencer Tracy in 1950 and The Caddy produced the memorable foursome of Dean Martin, Jerry Lewis, Bing Crosby and Bob Hope. This time Hogan made a cameo in the comedy, along with Snead, Byron Nelson and Julius Boros.

Medinah Country Club - No. 3 (1928)

If this was a Clubhouse Hall of Fame Medinah would be a first balloter - no question. Horse racing has Churchill Downs’ white spires, golf has Medinah’s Byzantine-flavored green domes.

The Ancient Arabic Order of Nobles of the Mystic Shrine, known better as the Shriners, organized in New York City in 1872 as a fraternal social club. The members had a fascination for the mystical lands of the Middle East, hence the name. Chicagoans especially took to the Shriners and by the early 20th century set out to build the greatest Shrine temple in America, with a banquet hall capable of seating 2,300 hungry Shriners.

To design the building that would consume half of a downtown Wabash Avenue block the Medinah Shriners picked two of their members, Harris Huehl and Richard Gustave Schmid. Schmid had trained under Henry Hobson Richardson, the greatest architect of the 19th century, but after visiting Istanbul and Baghdad to study Islamic architecture he traded Richardson’s Romanesque arches for Moorish onion domes.

It is easy to forget you came to play golf when you arrive at the Moorish-styled Medinah clubhouse.

In the 1920s the Medinah Shriners decided they needed a country retreat. And it would have to be big. They purchased 640 acres in suburban Chicago but it scarcely seemed enough with everything that was planned - two 18-holes golf courses, a 9-hole course for the ladies, a gun club, a baseball field, a swimming pool that would be the second largest body of water in Chicago after Lake Michigan, tennis courts, polo field, ski jump and toboggan slide. And an 11,000-seat sports arena and amphitheater. Newly opened Wrigley Field had a seating capacity of 15,000.

The focal point for all this athletic hustle and bustle would be a clubhouse designed by Schmid. Schmid brought along his Moorish sensibilities and went to work on his $870,000 budget. He constructed two towers, a campanile and a lighthouse to frame the 60,000 square-foot structure. The centerpiece is a 60-foot high rotunda. Schmid did, however, channel Richardson with his inclusion of bold entry arches and arched windows in groups of three.

The Moorish themes do not end at the porte-cochere. Gustav Brand, a long-time leader of Marshall Fields’ design team, decorated the interior with Egyptian-themed murals and capped off the elegant confection with a trompe l’oeil ceiling in the ballroom. Everything on the grounds was placed behind a Moorish-styled gatehouse.

Tom Bendelow was assigned the task of building the golf courses for the 1,500 members. He had the first one ready by 1925 and the last one, Course No. 3 intended for women’s play, opened in 1928. it was ultimately Course No. 3 that Medinah would choose to showcase. A.W. Tillinghast worked over the course during the Depression of the 1930s and the golf world stopped by regularly - three Western Opens (1939, 1962, 1966), three U.S. Opens, (1949, 1975, 1990) one U.S. Senior Open, (1988) and one PGA Championship, (1999) - before the end of the century. Byron Nelson won here and so too did Gary Player, Hale Irwin and Tiger Woods.

Woods won his first PGA Championship after holding off exuberant Spanish 19-year old Sergio Garcia who introduced himself to the American television audience by closing his eyes and slashing a 6-iron from the base of a red oak on the right side of the 16th fairway and onto the green. The tree, one of some 4,161 (each one was counted) on the course was removed a decade later after thousands of recreational golfers tried to recreate the shot in the intervening years.

Rees Jones was called in during 2002 to beef up Medinah No. 3 to 7,561 yards for the 2006 PGA Championship - the longest course in major championship history. The PGA of America found almost 100 more yards for the 2012 Ryder Cup which the European team took home by winning eight singles matches on Sunday.

While Bendelow’s work on No. 3 has been stretched and twisted to a point where he would likely no longer recognize it the club took a different tack on Course No. 2 and ordered a faithful restoration. Despite their one-of-a-kind clubhouses and grandiose setting the Shriners are a blue collar fraternal organization and Medinah was not a rich man’s club. Its solvency depended on numbers and when dues dipped during the Depression and World War II the club was forced to shut down No. 2 and members took over the groundskeeping. Membership was opened to non-Shriners. New members and tournament revenues kept the gates opened.

After No. 2 reopened none of the millions of dollars poured into No.3 was ever siphoned its way. Tom Doak did a renovation of No. 1 but by the time $3.6 million was freed up for No. 2 in 2015 Medinah realized it had an untouched Tom Bendelow gem and that money will go into a freshening and not a makeover. No. 2 will be one of the few among Bendelow’s more than 600 designs to make it into the 21st century in its original configuration. A one-of-a-kind original, just like the Medinah clubhouse.

Cypress Point (1928)

Alister MacKenzie put down a golf ball and asked Marion Hollins to hit it across an angry finger of the Pacific Ocean. Hollins, who had won the United States Women’s Amateur championship in 1921, hit the ball 219 yards and that is where Mackenzie sited his green for one of the most photographed par threes in the world , the 16th at Cypress Point Golf Club.

The multi-talented Hollins was the person responsible for MacKenzie being there in the first place. She was a master equestrian who boasted a men’s handicap in polo, the only woman to hold one. She traveled in fast business circles and was given the task of developing Cypress Point for Samuel B. Morse and his Pebble Beach Company. Seth Raynor had been her first choice for the job but he died unexpectedly of pneumonia with drawings on the table.

Marion Hollins, a former U.S. Women's Amateur Champion, drove Cypress Point into golfing royalty.

Hollins then turned to 56-year old Alister MacKenzie. MacKenzie had been trained as a surgeon and worked for the British army during the Boer War in South Africa. He was a club golfer before and after the war but when he helped found the Alwoodley Golf Club in 1907 and designed the golf course. He adapted camouflage techniques he seen the Boers use to make “artificial cover indistinguishable from nature” in developing the golfing grounds.

MacKenzie became more involved in golf architecture and in 1914 won a hole design contest sponsored by Country Life magazine and adjudicated by the British golf writer Bernard Darwin. Mackenzie’s par four hole allowed for five alternate routes to the green and was created by Charles Blair Macdonald as the finishing hole for his Lido Golf course on Long Island.

His budding golf design career was interrupted by World War I where he served the British Army as a camoufleur rather than a surgeon. When the war ended Mackenzie traded surgery for golf course destruction and in 1920 wrote a slender book called Golf Architecture which contained his “13 General Principles of Architecture.” He had not even designed 13 courses at the time.

The winning drawing of a golf hole helped launch Dr. Alister MacKenzie's design career.